Art by Artificial Intelligence: New Horizons or Worthless Imitations?

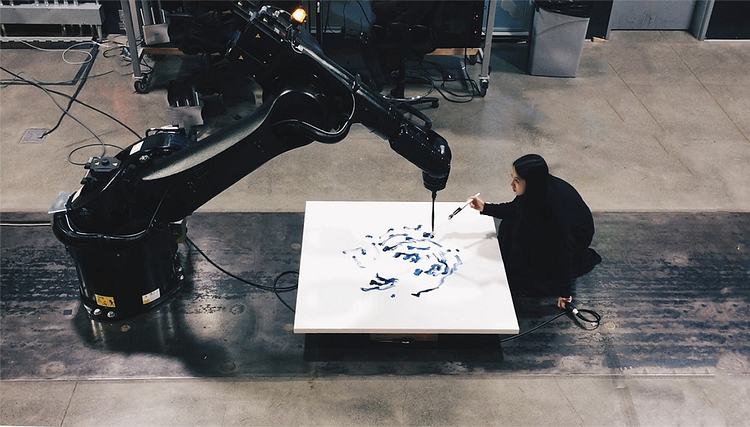

Featured image: Artist Sougwen Chung paints alongside a robot versed in her artistic style, exploring the collaboration between humanity and technology. (Sougwen Chung)

Artificial intelligence (AI), from the point of view of philosophy, is an attempt at recreating animalistic behaviour in machines. Those researching it are focused on the question, ‘Could a computer behave as a human?’, bringing forth discussions on what intelligence is, what personhood and identity are, and where thoughts originate.

Even René Descartes, back in the 1600s, considered this possibility and emphasised the idea that a test (like the Turing test, proposed three centuries later) needs to be available to ascertain who of us are ‘real’. This is explored in, for example, Westworld and Blade Runner (1982), wherein singularity has been achieved, and robots, who feel as ‘real’ as humans do, no longer follow Asimov’s rules of robotics, which dictate not to hurt humans.

From a computing science point of view, however, creating machines which can cognitively fool humans into believing they are humans is not a pursued aim. Instead, artificial intelligence is something that can learn from a pattern and make decisions and act independently—something which provides practical solutions for complex or repetitive tasks. Primary examples of this are self-driving vehicles, computer-aided diagnosis, and natural language processing.

But what is artificial intelligence from the point of view of art? Creativity is often understood as an inherently human activity of creation and expression, whereby we require human agency, original thought, visceral emotion and echoes of these, in some form, to be returned from an observer. Can a machine be a part of this?

How does a computer become an artist?

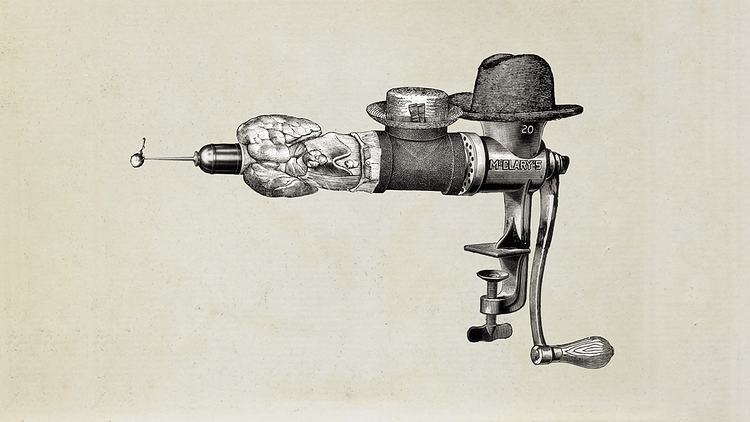

Ernst (2015) by Mario Klingemann's AI generative adversarial network, trained to create images in the style of Max Ernst. More images can be found here.

AI in art is used either as an aide in human creation, such as in the work of Sougwen Chung, or as an autonomous creative agent, such as AICAN. In this article, we focus on the latter.

Autonomous art-creating AI programs can already be found in music, in painting, and in animation. These software programs work by following a two-step method: first, they are trained on a set of examples; then they create something new based on what they’ve learned. The training set consists of the kinds of art we want it to mimic and produce: for some artists, such as Anne Riddler, the training set can consist of their own drawings. The training can be unsupervised (the computer is fed the data and is free to make its own rules and observations about it) or it can be supervised by the artists (the computer is told by the artist what to prioritise and what to ignore); the computer then produces something that is different from all instances in the training set but which still faithfully belongs to that series: an original piece work. In short, a computer is given many instances of how something should look, then it makes its own version of it.

This is not too dissimilar to the way a human becomes an artist: through training and study. We train our muscles how to hold and move a brush to achieve the visual effects needed to bring together a picture that’s either in our mind’s eye or which exists in the real world; we train our eyes to understand how a camera should be positioned; and we listen to music to learn how to make new music. Is this process fundamentally different from the above-described computer training?

Ingmar Bergman, a Swedish director who gained international acclaim for his work in film and in theatre, said in a 1966 video interview:

Ingmar Bergman, a famed film director, acknowledged that inspiration is brought forth through seeing things made by others and finding ways to adapt these elements to one's own art.

Similarly, the most common piece of advice given to young authors by seasoned ones is ‘read as much as you can’:

So what is really the difference between art created by a human and art created by a machine? Genuine difference seems to rest on the idea of originality. But, as we have examined, AI machines can learn new things, just like humans.

If art had a genuine ontology—if art held properties that existed outside of subjective experience—we’d be in a better position to judge because we might be able to train a machine how to obtain art’s objective properties.

Is there any objectivity at all?

Comedian (2019) by Maurizio Cattelan: an (overripe) banana duct-taped to a wall. This piece was displayed for a week, sold for over $100,000, then eaten by a performance artist in the gallery to 'create art'. Similar things have happened in modern art before: a cleaner cleaned up a modern art piece which she mistook for rubbish leftover from a party; Yoko Ono displayed a solitary apple in a modern art gallery in London which John Lennon took a bite out of; people have relieved themselves in Marcel Duchamp's iconic Fountain; and the Turner Prize given to Tracey Emin for My bed made heads around the world spin.

Pinning down exactly what art is is exceptionally difficult. We have explored this before with our resident artist. The definition of art depends on the point of view we take.

If we consider something to be a ‘work of art’, we mean it to either be a creative expression of some thought by the artist(s), or we mean it to be a medium through which we experience something by either viewing or enjoying it—something the artist intended for us to find. If the art has a practical purpose, we call the same process of creation ‘craft’. If the art has a commercial purpose, we call the same process ‘design’. The aesthetic judgement in qualifying something as art, craft or design, is up to us: we, individuals and groups as large as entire societies, decide what is and what is not art through experience and intuition. These definitions are unstable and fluid: something may be valued higher now than it was in the past; sometimes it was valued highly in the past but is worthless now.

The label of ‘art’ is therefore tested by both the artists who express emotion or thought in metaphor, and by the observers who receive the message and receive it in different ways. Both must agree that something is art before we can collectively say that is art or that person is an artist.

How does AI art fit into this?

What AI algorithms produce is artwork (e.g. a painting): they are taught what artwork looks like in literal ways through the training set to help their work become indistinguishable from that of a human. The result is an original instance of a piece of work as we understand it to be—we can agree on that. However, a potential issue is that the algorithm lacks what we usually call intent.

The AI artist, which in this case has a mechanical mind and a lines-of-code soul, learned its methods independently of the ways of its masters, and, in a way, ‘meant’ to create what it created; but it was designed to do so by a programmer and it ‘itself’ cannot appreciate its own creation. It has no freedom in it: it ‘knows’ no art beyond the training set, and it has no ‘experience’ of art, though it ‘understands’ brush strokes, composition, symmetry and what people find appealing—the computer becomes a real-life example of Frank Jackson’s thought experiment ‘What Mary Didn’t Know’.

Sean Dorrace Kelly, a philosopher at Harvard University, claims that any value found in non-human created art is coincidental:

Kelly here claims two things: art is an expression of a vision for human good; and an artist must display genuine creativity. He does not define nor elaborate on what ‘genuine creativity’ is and he does not comment on art which exposes or glorifies human cynicism, cruelty, or intentional harm.

Art is a medium for politics, too. A golden sculpture in the shape of the ICAR canned beef tins sent by international relief organisations during the Siege of Sarajevo was erected in Bosnia in 2007. The inscription reads: 'A memorial to international unity — grateful citizens of Sarajevo'. This is an entirely ironic monument: the ICAR canned beef tins were infamously 'so inedible dogs wouldn't eat it': the tins were leftovers from Vietnam war and were over 20 years expired, not to mention that they contained pork, delivered to the half-Muslim country targeted in the conflict. This sculpture is a commentary on work done by relief organisations, such as Unicef, during the 1990s Yugoslav Wars: a grand but profoundly empty gesture.

In line with Kelly’s claim above, Kant spent some time in his Critique of Judgement on describing what fundamentally makes art art. Works of art, he said, are objects that could be formally understood through pure contemplative experience. While we can each experience beauty in a personally interested way, there is also beauty for its own sake that only some people can appreciate.

Immanuel Kant postulated that an artist must not consciously follow the rules of art but be guided by some inexplicable, nature-given genius. But, paradoxically, he made a claim that ‘every art presupposes rules’ so the activity must be rule-governed and, in some way, every work of art must serve as a model or example of what a work of art is. He assumed a similar type of je ne sais quoi as Kelly: it’s simply a set of human skills some people are born with and which are irreplicable, in our case, by machines. But does this not leave very little room for ‘genuine creativity’?

Further, in Plato’s Republic Socrates, in a dialogue with Simmias after establishing that there exist perfect Forms of Justice, Beauty and the Good, speaks of Beauty thusly:

If we assume that there exists such things as ‘beauty’ and ‘art’ which are objective because they are nature-given, we can agree that AI art is ‘not real art’, but rather meaningless sets of coincidences. This, however, would imply that art is judged by nature-given intention and declaration of the artist, their emotion and their thought, and not for its own sake or for what it brings to the observer. Then what of the final product contains the initial genius? And why can’t machines produce it?

Whose expression is it?

Let us examine two statements made by Jackson Pollock, a prominent figure in modern art whose work pioneered abstract expressionist movements and whose paintings have been sold for millions:

- 'The modern artist … is working and expressing an inner world—in other words—expressing the energy, the motion, and other inner forces.'

- 'The painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through.'

These statements contradict each other: in the first, the painting is an expression of the artist’s inner self; in the second, the artist is solely the medium for the painting to come into existence.

But one of Pollock’s paintings, which hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, One: Number 31, 1950 (pictured above), was found to have been helped along by someone unknown after Pollock was done with it: brush strokes and paint not used by Pollock were discovered, potentially used to cover up cracks, and a fly which found its way to pink paint left traces of itself in the corners of the painting. So when we gaze upon it to either appreciate Pollock’s intentions or to go on our own journey of expression, we actually gaze upon something already different from what the artist intended and what the painting wanted to become through Pollock. Yet the emotion felt by the observer is no less real.

Leo Tolstoy had much to say on what is and what is not a work of art, emphasising the relationship between the creator and the observer and the emotion that must be passed from one to the other:

I can relate to these words and reflect on my own experiences: when I view William Turner’s Snow Storm I feel anxious, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers bring me joy, some poems bring me to tears, some films inspire me, and some books change the way I feel about the world.

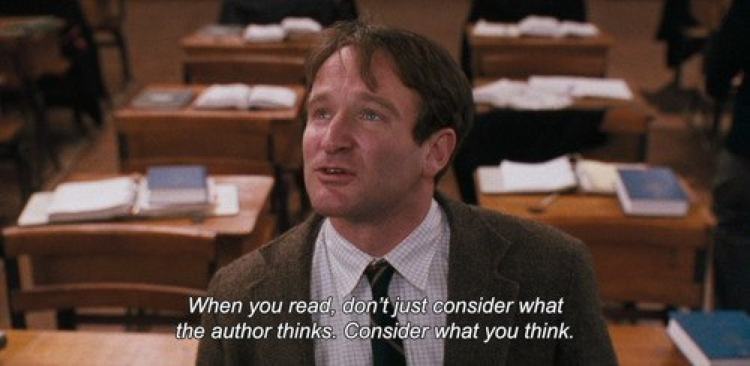

In Dead Poet Society (1989), the students taught by unconventional English teacher John Keating (Robin Williams) are encouraged to analyse poetry for how it makes them feel instead of analysing it by what their textbooks told them to appreciate within its verses.

Plato (through Socrates) and Kant disregarded the observer’s presence. Their take would place art created by AI into a clear-cut ‘not real art’ category by virtue of not being made by a human and thus existing without ‘reason’ or ‘genius’. But the idea that the observer’s subjective experience in deciding what is and what is not art is unimportant is ambitious in the way it connects some humans to objective beauty, whatever that may be. Our aesthetic preferences are frequently culturally determined and changeable: is objective contemplation of what art is such as they suggest even possible? Our reception and interpreation of art and the emotions it elicits are the reasons we value art in our lives. We use this power to choose our clothes, select the books we read, decorate our homes, express who we are, and how we subjectively perceive the world.

The relationship between expression and experience, I would argue, is paramount to the existence of art. And whether a trained artist made it, a computer made it, an artist made with a computer’s help, or a child who has yet to learn to walk, experience the world or learn the names for the feelings they experience made it—if I find value in it, how can anyone claim it isn’t art?

'That's one of the greatest things about music. You can sing a song to 85 000 people and they'll sing it back for 85,000 different reasons.' — Dave Grohl

It's up to you

Humans have a desire and capability to use symbolic thought to ponder and then convey feelings, intent or some unutterable truth. A sprinkle of skill, a dash of emotion, complexity, and evocation of visceral feeling—and it’s hard to deny some works of art have greater weight than others which reach bigger audiences and persists through time.

But art can come from anywhere and can be described as such by anyone. The value brought forth is in the eyes of the beholder: it need not be influential or sell for thousands of pounds to evoke real, authentic emotion in the observer. The artists need not be trained by household names to convey a deep message, nor does the artwork itself need to be judged on the artist who made it. Whether a trained professional, a child, an animal, or a computer autonomously created something, if it means something to you, it simply is art, regardless of the qualifications of the artist. In this sense, art created by AI can be seen and felt as art.

What a Loving, and Beautiful World: an interactive digital installation by TeamLab. The scenery changes as the visitors interact with the space so each moment of viewing the installation is unique, just as every moment we interact with nature is unique: a breeze strips the tree naked of its leaves; a bird flies away when we approach.