Celebrity Culture I: The Attention Seekers

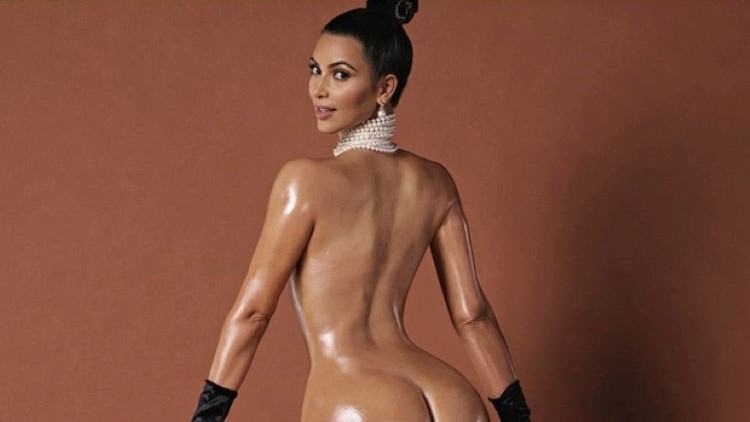

Featured image: Kim Kardashian attempts to 'break the Internet' with her naked body. (PAPER magazine)

Isn’t it curious how we can be utterly engrossed by people who lead completely intangible lives to ours? Celebrities plea for attention; we mindlessly oblige them. Their lives permeate what we see, what we hear, and what we read. What compels us to care? What does it say about us?

I’ve scarcely been one to indulge in celebrity culture. In fact, those that know me well may wonder why I’ve dedicated any time at all to write about it. I could just refrain from delving deeper into something I have no interest in. Moreover, however superficial the culture is, people clearly enjoy absorbing it: why try to disenchant them? Well, to begin with, this is a system that is so effective at garnering our attention that I believe it warrants closer inspection in itself. It’s suspicious and I want to explore how it affects us: maybe there is more than meets the eye. In a world where a former TV star is the President of the United States of America I can’t take the situation too lightly.

What is a celebrity?

Celebrity culture belongs to the world of show business, where entertainment is the main product. This world stipulates that those who receive the most attention have mastered their art, for they are, superficially, entertaining the most people. There are rules for how one can maximise their reputation—things they ought to. This blueprint celebrity model illustrates a well-trodden path that many people have beat their feet down upon to make names for themselves—loss of privacy, endless interviews, increased pressure, employed advisors, and so forth. ‘Success’ requires thankless hard work and ruthless self-promotion. There’s only so much room atop the celebrity mountain; piled bodies scream for attention on the peak. People have to really want celebrity status to stick out. Why do they put themselves through it?

Two primary goals are wealth and fame, it seems. Charlotte from Geordie Shore and Barack Obama are both considered celebrities but I challenge you to draw parallels between the two. Nevertheless, fame and wealth are common identifiable features between them.

Somewhat surprisingly, talent isn’t essential to attaining either of them. Merit is an immaterial property in this strange realm, in which so-called personalities can bask in disproportionate levels of undue adoration.

There are, of course, numerous talented celebrities who are probably worthy of our interest by virtue of merit and who are wholly competent at their jobs. Beyoncé and Leonardo DiCaprio aptly exemplify this point. However, many of these people solely covet the fame and wealth they receive: they want these hollow markers of success, not necessarily any earned success. It is these people who are in my firing line. How and why do they engage our fascination?

Charlotte Crosby, famous for appearing in Geordie Shore, enters the Celebrity Big Brother House, captivating millions in the process. (Ian West/PA Wire)

The celebrity model

It has been argued that celebrity culture was born as early as the 18th century, when the proliferation of portraits and cheap image printing facilitated intimate, not-always-flattering insights into how public figures live (sound familiar?).

At a human level this engages us because we are nosy enough to peek into the lives of others and to reassure ourselves that even great people consist of flesh and bone.

Voltaire unbecomingly depicted in his private life. (Le lever de Voltaire by Jean Huber, 1772)

One can easily imagine how public engagement, in general, could be put to good use: our society can always benefit from collective scrutiny and criticism. But consumerism has perverted this potential. An increasingly financially driven and digitally connected society has bred a mechanism which acts to generate fame for particular people. By being carried by mass media coverage and by pandering to human curiosity celebrities exploit us. They need us to buy into their lives to sustain their careers.

Celebrities augment their wealth when we consume products associated with their personas. The process can be direct: we may be more inclined to buy products, such as perfume, butter, motor insurance, or fitness tutorials, that have been endorsed by recognisable faces. The process can also be indirect: watching, listening to, and reading about these people promotes their relevance in our minds, manipulating our purchasing patterns to be in their favours.

Celebrities require consumers.

This is a system that is cold-heartedly efficient at smothering every facet of our existence. What chance do we really have? As writer George Monbiot puts it, ‘It is pointless to ask what Kim Kardashian does to earn her living; her role is to exist in our minds.’ And, indeed, her and her team have succeeded at capturing our attention.

Kim and Kanye. (Harry How/Getty Images)

It would be easy for celebrities to make us feel comparatively inferior and unimportant. But celebrities are prudent. They deploy all kinds of tricks to appear relatable.

Celebrity selfie, Oscars 2014.

A cunning trick is to masquerade their lives as highs and lows that are universally experienced: stories gain more traction when they are personal. ‘X is cheating!’ ‘Y is pregnant!’ ‘X and Y file for divorce!’ Delivering contentious statements or otherwise acting controversially is another approach to appearing relatable; it reminds us of their fallibilities.

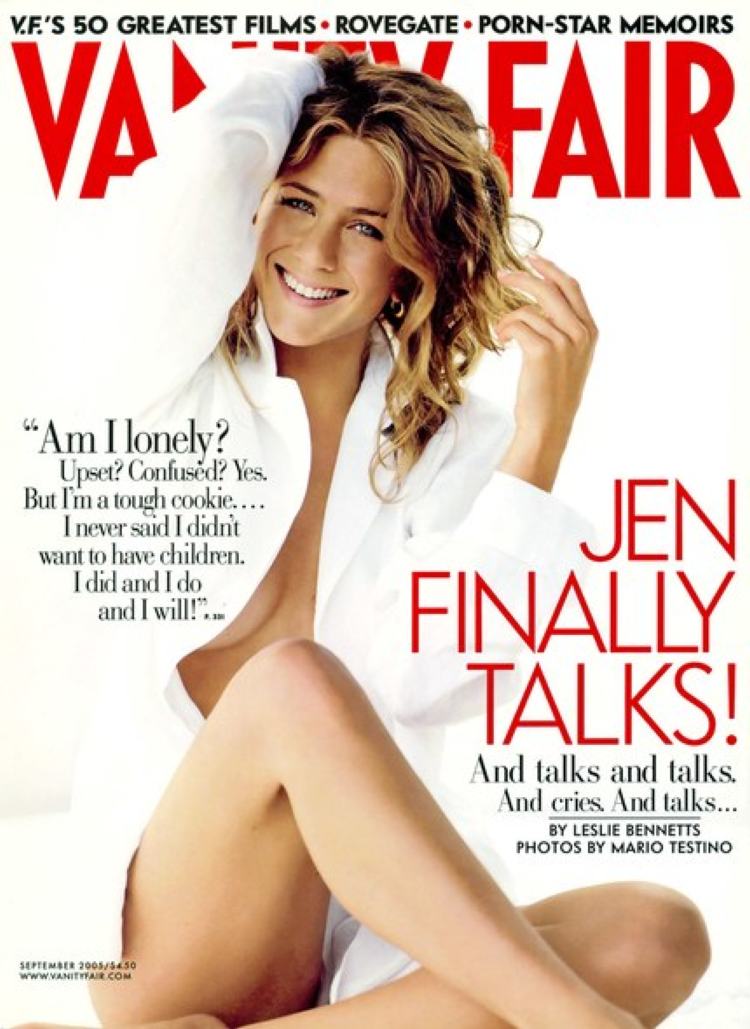

'Jennifer Aniston finally talks!'

In terms of the propagation of their personas, various methods are employed to provide us with what feels like personal insights into their lives: we follow them on social media to gain a sense of intimacy; journalists document their lives in tabloids and glossy magazines; the paparazzi photographically expose them; we watch reality TV and chat shows in an attempt to understand their personalities and observe how they interact with people; and so on. Equipped with these tools, the system is sufficiently powerful so as to catapult almost anybody into fame, where we are the consumers of this unreservedly huge market.

Introspection

So it’s lucrative to be a celebrity; I think we all knew that. Money aside, celebrities aren’t that different to you and me, though. To a degree, each of us feels the desire to be adored; to feel a sense of importance. We seek ‘followers’, ‘likes’, ‘hits’, and ‘shares’. We revel in popularity. Going viral is a momentous achievement. Why?

The draws of recognition are inherent to us all. It informs us that we’re doing things right. It also positively reinforces our behaviours and increases our confidence, which is empowering since high self-esteem enables us to lead the lives we want to live. As such, gratifying this appeal is a completely human self-assuring strategy.

But when we overly rely on society’s approval the views of others can play a significant role in how we define ourselves. This form of validation—being reassured that we’re adequate—forms only a temporary state of satisfaction. Detrimentally, if we afford too much credence to self-perception, our happiness is always going to be at the mercy of others’ judgements.

Those who crave approval and those who pursue financial reward to demonstrate individual success possess inflated desires to be reassured by others. Fundamentally, this paints an already-abject picture of unfulfilled selves—insecure, discontent, and, at times, narcissistic—but celebrity culture, I believe, has shamelessly pandered to these traits and exacerbated them. Many celebrities and those who envy them are caricatures of these behaviours, for they are desperate to be perceived as successful in a society or, at the very least, relevant as they devise ways to thrust themselves upwards accordingly with certain life choices and social media content.

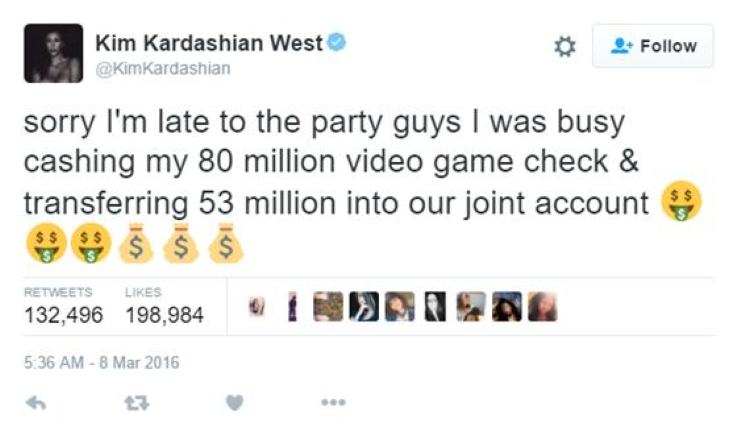

An ostentatious tweet to 50 million people. Success, at least in Kardashian's mind, has been monetised.

We only have to look as far as TV to epitomise the unrealistic and materialistic dreams of a nation obsessed with fame and wealth through celebrity culture: The X Factor, led by a mogul with a net worth of £330 million, has contrived a notion of success that exploits the desperation of people to be recognised. A contract, with which people have little control over when it comes to creating music, is the prize along with often-temporary fame. Hundreds of thousands are pitted against each other but very few can succeed. Yet millions of us tune in for musical performances and for manufactured personal stories that might resonate with our desires to witness regular people reach the ultimate stage of stardom.

Then there are shows like Big Brother and Love Island, which the same notion of success. After they take the stage they immediately ‘earn’ celebrity status. Prominent appearances or full-time role in showbiz follow, beckoning them further with the temptations of fame and wealth.

I’m not making the point that we can simply omit our inherent desires to be acknowledged from our psyches. Can you imagine how frustrating it would be if our accomplishments were never recognised! Nor am I saying that we shouldn’t enjoy showbiz as a mode of entertainment. Rather, I argue that celebrity culture is built for celebrities first and foremost; that it makes many of us want to follow in their footsteps to reach status and fortune; and that it’s an unfair game with limited space at the top that, ultimately, can damage self-esteem. Why? Because celebrity culture nurtures exaggerated illusions of worth, which, for us, often leads to disappointment and insecurity when we can’t emulate their success.

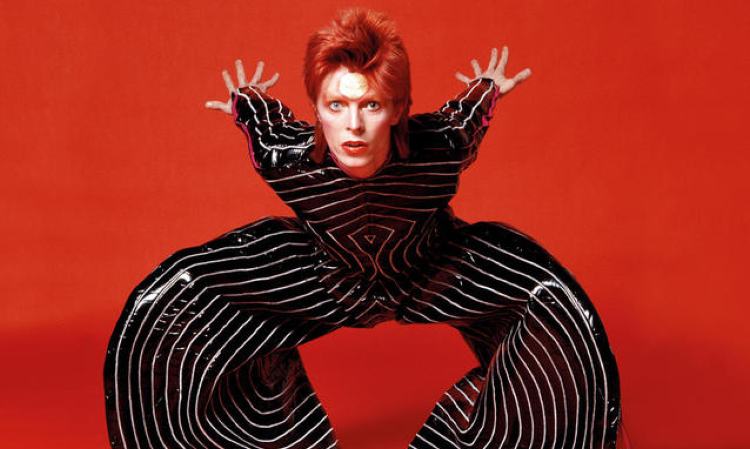

But are there noble ambitions of fame? Indeed, there are some good reasons to pursue it. The great David Bowie, for example, chased stardom to gain greater access to resources and a wider audience, for he possessed what he saw as grand ideas that he wanted to impart on others. ‘I wanted to make a mark,’ he’s on record as saying. This is something I can relate to, at least. Indeed, many of us wish for our philosophies to resonate with people and for our work to positively impact society. Feeling valued, not excessively adored for playing a game of questionable merit, to me, seems normal.

David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust persona.

However, although Bowie purported to not want to be a celebrity—he declared that ‘fame itself is not a rewarding thing’—even he sought to become an icon beyond music. He tried everything he could think of until the end of the Sixties to build traction, including different costumes and personas, until it all came together. He required the attention of an audience to find out more about himself, whilst later in his life his music became autobiographical. Essentially, then, did he just seek a more sophisticated form of validation of his unconventional self?

Either way, from us and to them, from Paris Hilton to Prince, at the core of celebrity culture is an attempt to engage our insecurities and to entice us with the lures of fame and wealth to varying extents.

So what?

Isn’t celebrity culture merely an innocuous form of enjoyment?

I appreciate the entertainment value that showbiz delivers to us; however, an incomplete perspective leads us to dismiss the non-trivial consequences of this self-serving culture.

Celebrity presence is so ubiquitous that it should come as no surprise that our values have changed as a result. In 1997 TV content for 9- to 11-year-olds was mostly associated with community feeling and benevolence. But by 2007 these values had fallen from 1st and 2nd to 11th and 12th and were superseded by fame, image, popularity, and financial success. I find this rather striking and, actually, quite scary.

These cultural effects are particularly pertinent to the insecure and the impressionable. Of these people, children are probably the most susceptible since the young mind can be absorbent and directionless. Furthermore, they are under tremendous amounts of social pressures already. Thus ask children of today what they would like to be when they’re older. No doubt, many will want to emulate their celebrity role models and dream of experiencing the distant lives they lead because ‘success’ culturally emanates from them.

Bieber fever. (Reuters/Shannon Stapleton)

Moreover, authors of another study found that people who were most engrossed by celebrity culture were three times less likely to be involved in local organisations and half as likely to volunteer than those who were most interested in other forms of news. They concluded that those who followed celebrity culture were least likely to be politically engaged. Again, this is an indictment of our society. Surely we can do better.

An alternate vision

The society we coexist in has built a system that suffocates consumers with the relevance of celebrities, who actually depend on us. Not only is celebrity culture a money-making machine that spuriously conflates fame with genuine achievement: it’s an ugly and distorted growth from something intrinsic in all of us, for growing oneself successfully—flourishing and contributing— is existentially satisfying.

However, relying on external approval in order to achieve internal harmony, without addressing our true passions or holding humble goals, is perpetually unfulfilling since this places self-esteem under the behest of others. It’s better to look within first. At the outset people who covet instant success and influence with a celebrity status play a hollow game. They try to please others with their appearance and the content of what they say and let people define what their achievements should be. To cultivate favourable reputations they also curate idealistic online identities in attempts to live up to impossible standards. But, we must all realise, this is futile and dishonest for the majority. Alas, many still aspire to be famous and wealthy and do not seek to discover their role in society first before finding its place.

Despite all of this, I remain cautiously optimistic. That is, if we can free ourselves from the constant urge to prove ourselves to others, self-perception will no longer be a prime determinant of happiness. We can be lauded for our success when we’ve truly earned it. And so, with more humility and more introspection, there is hope for each of us go-getters yet.