The Human Identity Crisis

Featured image: Christian Bale as Pat Bateman in American Psycho (2000), a black comedy adapted from Bret Easton Ellis' novel.

Unless you are an identical twin, no one else on Earth will ever share your genome: you are born unique. You are therefore universally unmatched, always distinguishable. You are a continuously evolving product of complex interactions between nature and nurture. You are an individual.

We are free to express your individuality, enabling others to better understand you through your beliefs and your actions. Yet so often this is not our chosen path. We choose to do the complete opposite: we choose to conform.

This irks me. It irks me because individual expression is a beautiful concept. To rebel against conformity is powerful and courageous; to conform to what is deemed socially acceptable is predictable, mundane, and completely unoriginal. Conformity tears away everything that is interesting about you, reducing you to a replica who conceals their insecurities behind a monotonous façade to appear relevant.

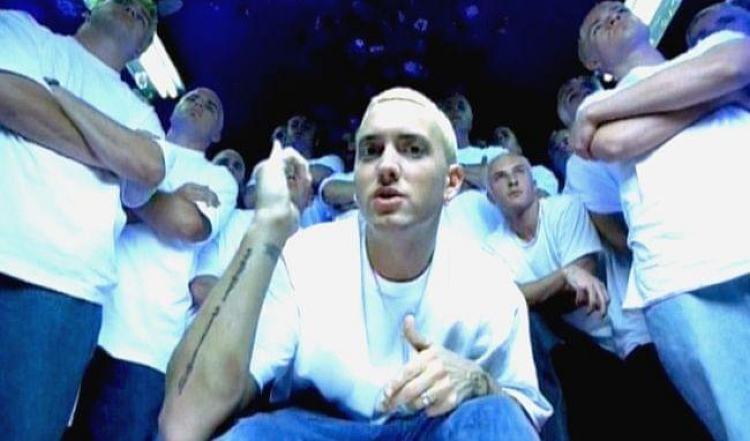

Will the real Slim Shady please stand up?

I cannot see anything perverse in expressing ourselves or seeking to build self-esteem through identity. Nor is there shame in trying to decipher one another superficially. After all, we impart first impressions on people and our style enables people to understand the ‘us’ beneath the attire we wear better.

But there is an internal battle here: we want to fit in with current trends and we want to be noticed as the unique individuals we take ourselves to be simultaneously. The two are mutually exclusive.

Bret Easton Ellis, one of my favourite authors, is the king of commentary surrounding this topic. In American Psycho, perhaps his most-incisive work, he mocks conformity through black comedy with absolute precision. It is brilliant and perhaps a good basis of my arguments here. I will not ruin the story for you if you have not read the book or seen the film that followed. But I will borrow the narrative.

Amusingly (and horrifically) Ellis describes how mundanity is driving everyone insane in Eighties New York. The characters are caricatures of yuppie investment bankers who are all, naturally, trying to outdo each other, be noticed, and be respected. But, at the same time, they want to fit in. Everybody is obsessed with earning lots of money, sealing big deals, and wearing designer clothes. But this renders everyone the same slick-haired, identically suited, money-obsessed, decadent lunatic. Consequently, everyone sees subtle differences between one another as hugely significant signs of success. This drives the antihero, Patrick Bateman, who craves recognition for whom he really is—a monster—insane.

Take one of the most-famous scenes from the film, in which the pedantry surrounding who owns the best business card satires the race to be noticed, even though for most people the differences are utterly trivial. American Psycho serves a stream of similar examples. Obviously, they represent exaggerations of reality but sometimes this is required to demonstrate a point.

Many of us share that same great, conflicting urge to stick out but fit in as Patrick Bateman. This tendency is apparent if we consider how we allow ourselves to be dictated by fashion trends on a daily basis. We worry about how people perceive us. So we allow top brands, given an increasingly consumerist and materialistic society as a backdrop, to override our individual identities.

For example, take companies such as Jack Wills and (old) Abercrombie & Fitch. A major cause of their successes is how they have tapped into peoples’ perceptions of class and social status. By buying an extortionately priced gilet from a store decorated in wood chippings, bunting, and owls—a store we are waved into by ‘attractive’ employees (‘hardbodies’ in American Psycho) who are paid to stand there and welcome you in—we are arguably made to feel special and above everyone else. But beneath the fabric the same person exists.

Jack Wills, Winchester: Look at the guitar! How wonderfully quirky and imaginative.

Yes, you can argue that, by going to such stores, you are paying for the better stitching and longevity. While this might be true, I believe there is a deeper desire in us: a desire to reassure other people that we belong to certain ranks of society. We hide in cliques, surrendering individuality to fit into them.

Conformity leads to such a strange conflict: we think we will stand out from certain crowds by going for clothes of particular styles: the result is to become unoriginal and unfaithful to ourselves, however niche we think we are being. In conformity we seek to be noticed by our peers. What we achieve is to plagiarise others to disguise our own lack of originality. ‘Fitting in’ cannot mean ‘being you’ because you have to surrender some small part of yourself with each choice you make (that is, if there is a real ‘you’).

I used to think a lot about this at school because peer pressure completely baffled me. I wanted to be cool but I wanted my reputation to stem from who I actually am, not a template. There was no solution: I couldn’t stick out because, by being cool, I would look like everyone else!

Another person with the same clothes of the same brand with the same haircut. What are they—what am I—seeking?

Of course, our teenage years are full of social pressures that are unmatched across the rest of our lives. We expect juvenile behaviour from insecure and immature teenagers, who usually want to fit in. Perhaps this is a necessary process in our formative journeys. I was surprised to see this continue into adulthood.

To this day I am on the receiving end of mockery (‘banter’) for not conforming to certain trends (though this is never explicitly stated as the reason why). I never really understood why being myself made me more susceptible to insults but it did. I am more mature now, so I can make sense of it. But back then it required tough skin to deal with it. For example, a friend of mine once said to me: ‘Do you ever wonder if you were born into the wrong body?’ What this person was trying to convey was that I, a person whose passions attract negative stereotypes—greasy, nerdy physicists; angry ‘metalheads’; uncouth men of football—did not belong in the biological vehicle that was my body. That the aspects of my life that I derive enjoyment from are intrinsically related to one of these demeaning stereotypes. This is an outrageous thing to say; a horrible insinuation. Clearly, in her eyes, I would have fulfilled my social potential in conformity by acting like and being adorned in the same clothes as everyone else. My desire to be myself was something she did not understand.

A 'nerd'. Does he dress in a nerdy style to match his self-perceived identity?

This comment was just one of many personal judgements I received and observed at university—a hub of seemingly well-educated adults—and after. If your jeans were not tight enough, your shirt not sufficiently checked, or your wardrobe not a conveyor belt of much-coveted attire, you were outed.

To me this all screams ‘insecurity’, where the most-insecure, deep down, hold the biggest doubts about who they should be because they live as someone with the most conviction. Their insecurity, I think, is rooted in the Human Identity Crisis—the fight to be heard in the internal battle between individuality and conformity. Each side offers a form of emergence, an actualisation of self to be regarded by others, but each side is antithetic to the other. So long as both are available we do not know, with certainty, which to choose. This breeds existential doubts that can only be dissipated when we surrender our convictions. Reality is ambiguous: we are individual beings; but being individuals means nothing if we aren’t heard by others.

Being comfortable with ourselves requires accepting individuality but also the fact we can never truly be unique. The trick is to express whatever it is we think is authentically ours. Only now can I see it.

The people who ridiculed me acted like conformity was the only option. They hid their individualistic identities; let them fester as insecurities. By ridiculing other people, they reinforced images that weren’t their own.

Ultimately, I am glad that I did not surrender myself to group identities too much. I remained as true to myself as I wanted to be. This was my process of self-discovery, my choices; and even if they were not original, I felt in charge of them.

Buy your hipster gear here! A countercultural statement is the so-called 'hipster' movement. But the hipster image—an attempt to dissent against the status quo—still fits into a collective symbol. It can, therefore, be seen as an ironic expression of individuality, a pseudo-rebellion against what is popular. We are not original: we just think we are. I am not a hipster—at least, I do not identify as one—but my scathing views on pop culture, my ear jewellery, and my inclination towards independent movements of individual empowerment points to a similar scene.

So am I being hypocritical? Possibly. But I seek to express myself authentically in order to engage people with whom I really am so as to feel understood. There is no intention to follow anyone nor is there a stubborn stance against what is popular or what is not. I just express myself in ways I critically take to be authentically me, knowing that these values are shared by like-minded people. Of course, many people authentically express their true selves. But many do not know their true selves yet: their internal values are hidden by the external values they only superifically adopt.

Endeavouring to fit in for its own sake disregards individuality. Conformity only provides a flat and numb kind of security that will safely lead you to insanity.

I commend true expression: it requires courage. Those who seek not to follow but to think for themselves usually have something interesting to say: they tend to find an answer that means something to them. Ironically, they lead the way for everybody else.