Ego II: When Ego Spirals Out of Control

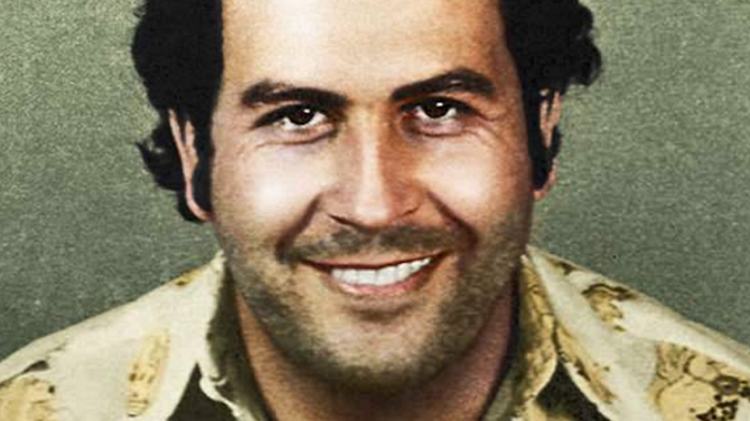

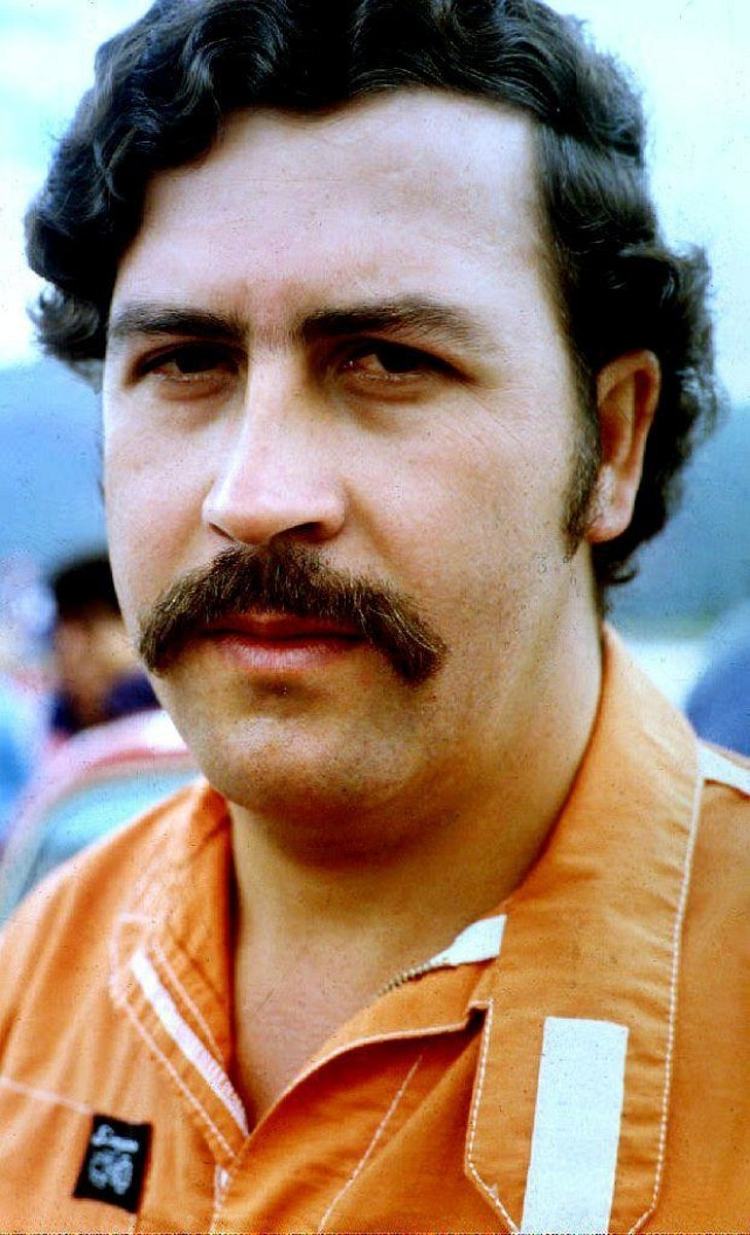

Featured image: Colombian drug lord and narcoterrorist Pablo Escobar.

We all feel ego’s influence. Even if we don’t want to acknowledge it, the chance to feel important entices us. It gives us this aspiration—makes us seek approval, accolades, and validation and want to have a long-lasting impact on society. It provides the fuel for our burning existential aspirations to be realised in the world.

Surely, then, we should indulge ego, not dispel it: it confers to us self-interested but authentic motivations that can be harnessed for common ‘good’. Authentically motivated people are genuinely ambitious and catalyse personal and communal projects, from political movements to work. All we have to do, if we are to harness their potentials, is reach into them to find the truest of motivations and orientate these motivations towards the group’s.

However, as per the arguments of this article, tapping into ego too much leads to egotism. In turn, people begin to listen to themselves too much and their motivations become incongruous with the rest of the group’s: it’s their way or no way. Consequently, they overestimate themselves—they become totally self-absorbed and overindulge their own views—and stop listening. In doing so they restrict their learning and prevent many goals from being realised. Their desire to demonstrate self-worth is so obsessive it’s almost pathological. Because they want to feel really important, they sacrifice wisdom and humility; they risk delusion. While in the mirror they see greatness, through the glass we see sad and wasteful hubris.

There’s a scale here, though, and we should heed it, for ego’s slope is slippery. Where’s the line? While we might not be egotistical now, if we continue to act with too much confidence and not enough self-scrutiny, we are at risk of succumbing to egotism, a profoundly ugly state of mind, unbeknownst to ourselves because we love ourselves too much. That is to say, in delusion, our perceptions of ourselves are disjointed with everyone else’s.

The first step toward preventing this—and to ensure our desires to feel important are utilised to ‘do good’—is recognising the characteristics of a bloated ego. Fortunately, multitudes of people throughout history can exemplify them for us.

The Deadly Sins

Egotism manifests in a number of recognisable ways—ways that most people don’t want to acknowledge as traits in themselves. But we should take notice if we care to avoid them.

Negative attitudes towards ego are reinforced by proud individuals flattering themselves whilst dismissing the importance of others. Donald Trump, an egotistical person, clearly sees importance in himself as he puts down peers. He makes our collective success his success. He’s overtly inwardly concerned.

The caricatural figure of ego is someone, like Donald Trump, who holds lofty perceptions of themselves. However, their actual qualities don’t live up to their expectations, making them excessively proud of who they are: their qualities aren’t met in the real world. By definition, such pride is arrogant, especially if it is present alongside contempt for others, who they consider to be of less importance, which it usually is.

People who possess this vice are obnoxiously conceited—unpleasant to be around. Mirrors are magnetic. They flaunt, they boast. They defend their honour and they treasure victory at all costs. Pride must be maintained, for they are the vainglorious!

'I prefer to be in the grave in Colombia than in a jail cell in the United States.' — Pablo Escobar, whose arrogance ultimately led to his death.

The flush of pleasure associated with a sense of pride is not abnormal nor should it be discouraged: it’s right to feel good about our achievements. But vanity, the result of successive superlative self-assessments, is a vulgarity which isn’t even conductive to success. Frequently, it fails to guide us objectively to achievable goals and leads to feelings of frustration and unfairness and a tendency to blame others for our failures.

The pretentious murderer Patrick Bateman, the American Psycho (2000): the man who, superficially, possessed everything an ambitious 26-year-old professional should possess. He received so much external validation, bestowing to him an inflated sense of self. But none of the validation he received ever fulfilled him because, in playing up to the expectations of his culture, none of it was rooted in true understanding of self. He played a role he didn't choose so he pushed every boundary he could to try to find respite. But respite never came because none of those people saw him the way he saw himself; none were willing to believe him to be the heinous monster he felt he was capable of being.

A sign of egotism in someone is their constant craving for validation from their surroundings. Those who betray the greatest levels of egotism yearn for popularity over all else; their egos pine for it. Burdened by a really favourable opinion of themselves, they must constantly prove to other people—and, by extension, themselves—that they’re important. When they demonstrate their notional worth to others, who, in turn, praise them, their self-importance is validated, giving them peace of mind. Their beliefs feel genuine as they have now been actualised in the real world, through people, and no longer left untested in a private reality.

Egotistical people incessantly disseminate the details of their lives. We recognise such tendencies in public figures, who revel in global audiences. But we also see the need to be validated in our friends. Regardless of what they see ‘success’ to be—social media popularity expressed as followers and likes, house and family, ability to free-spiritedly travel, larger amount of wealth accumulated—our seeing or hearing about their lives at machine-gun frequencies delivers to them their daily doses of validation.

Egotistical people strive to accomplish widespread traction between themselves and society, where possible, to remind them of their own relevance. This form of ego-pandering has been encouraged during an era of celebrities and the Social Media Age as outlets for expression continue to grow in number and facilitate our vain expressions. But human nature didn’t begin at the advent of Myspace: such longing for recognition has always accompanied humans. It’s only now that we can tangibly leave marks to feature somehow in others’ lives. Throughout the ages only few have been able to succeed in not fading from history’s pages.

Ego's remit even transcends mortal life: my ancestor and namesake, Sir James Clark Ross, lives on in a painting, which depicts significance beyond his natural 61 years. History illustrates that we're lured by recognition—not just now but beyond the grave. Momentous achievements are rewarded with tales of courage, statues and monuments, and names of roads, months of the year, and buildings. It might be irrational and futile to care about our reputation subsequent to our passing but, existentially, we can't help it: we're concerned with the immaterial survival of our identities, of a wish to go on unbounded. Perishing with marred reputations would be painful; thinking we'll be remembered positively alleviates existential frustration.

In many of our behaviours we show that we want to be validated, for we want reassurances from others that we’re doing the right things. However, while these behaviours are apparent in people with low self-esteem, validation is reached out for by egotistical people to satisfy sizeable senses of self-importance.

In fact, they overly rely on these interactions. Seeking validation through sex, for instance, is common: I like that someone else wants me. Attracting people instils a sense of self-worth; sleeping with them consummates it. Those who relish the chase and covet the subsequent success in voluminous proportions demonstrate egotism to the utmost degree. However, this only leads to fulfilment if the essence of someone that’s being validated, not an idea of them. That is to say, if you have to mislead a sexual partner by pretending you’re somebody else, you’re not validating anyone: you’re participating in a physical transaction that arms you with a cunning weapon of deception, to them and to you, and your existential pursuit will stay fruitless.

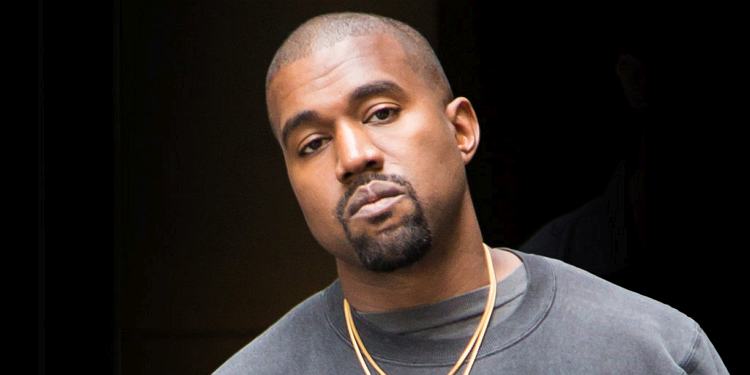

'I want you to document this right here, what I'm saying right now. I am the number one human being in music. That means any person that's living or breathing is number two. Because I'm number one now … You are in the presence of the champion. Bow in the presence of greatness … ' — Kanye West

Egotistical people lend their fidelity to lies. They have to because they rate themselves so highly their realities become unobtainable. So they have to choose between lies and failure. Giving into the former, the fantasies they create, featuring themselves, are easier to deal with than life’s harsh realities. But they divorce themselves from the real world, where falsehoods serve the purpose of reassuring them that they are exceptional. This is a precarious state of mind because it starves one of true, believable satisfaction—a coping mechanism containing a ticking time bomb.

Most people have met deluded people. Their delusion is recognisable in their wild lies to people usually with regard to their achievements. In extreme cases the symptoms of their egotism are not too dissimilar to those of psychiatric disorders—for example, if they’re prone to believing that people are infatuated with them or if their claims are grossly exaggerated.

It’s true that some happiness can be found in the art of fabrication, in leaving positive impressions. But whose glory do these egotists bask in? Not their own. Every day they face a lie as they begin each task unstably and unconfidently, not knowing whether they can truly grow outwards into the world.

Empowerment to enact genuine change must come from within. The protagonists in the film Inception (2010) understood that all humans, to a degree, are fundamentally stubborn in nature. Cobb et al, therefore, developed a method of tricking individuals into thinking ideas are their own. We sometimes have to deploy inception in real life too: we have to implant ideas into people's heads for common gain. In the workplace, for example, appraisals are orchestrated to guide workers into constructively criticising themselves. Their managers hope to increase their productivity.

The primary way the egotistical believe in is their way. Any attempt at convincing them otherwise is futile.

They have dogged determination to prove that they are right, for they just are never wrong. Mistakes are never theirs: the faults belong to others. External voices, particularly instructions that challenge their power and leadership, are shunned: they don’t need any help. Criticisms are taken badly. They weren’t bested: they just didn’t try. There is no unconscious: they consciously make all of their decisions. Everything is done on their own accord.

We can't just tell these people that they're wrong: it achieves nothing. Fruitful debate, for example, only begins at understanding where your opponent is coming from. Our input is otherwise rejected and we're waved away. (Bobmadbob/Getty Images)

The critical problem is that human beings, in virtue of our egos, reveal time and time again that they’re capable of being magnificently wrong.

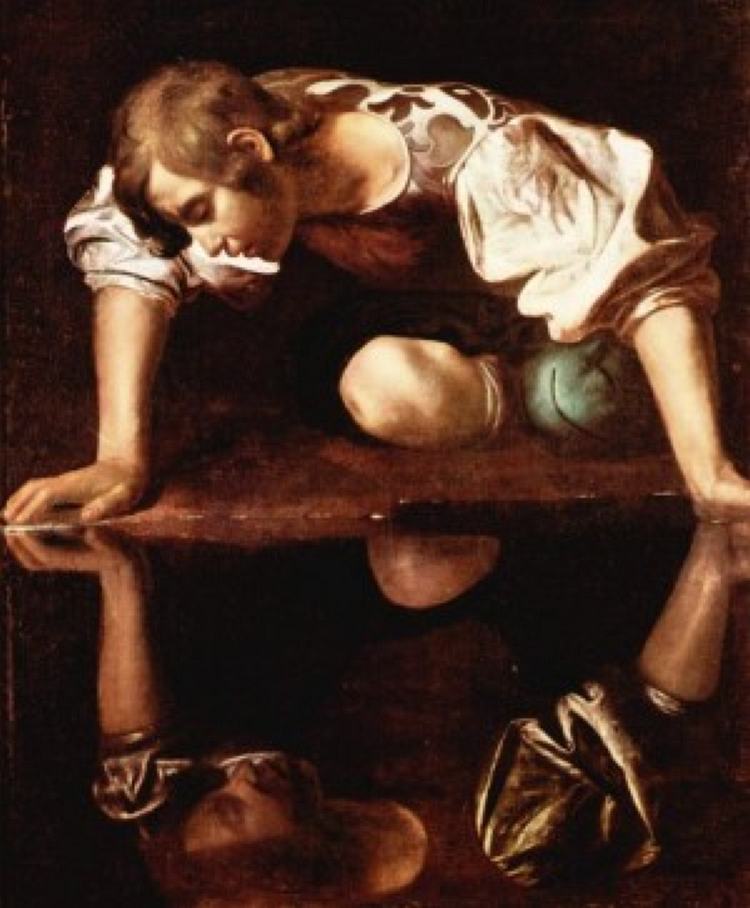

Narcissus by Caravaggio: Narcissus, from Thespiae, Boeotia, was drawn to a pool in the woods, in which he saw and fell in love with his own reflection. He became so obsessed with his own beauty that he ended his own live: his love for himself could not be reciprocated.

The pool of self-indulgence is something we all dabble in. It’s evident from the jobs and hobbies we dream about. Take creators (e.g. artists, musicians, filmmakers, writers, etc.). Their success pertains directly to their individuality. Social media is packed with this brand of self-indulgence too. Likewise, why have I written and posted this article? My desire for my views—my agenda—to be shared with you and understood, not hidden, is a sign that I value their dispersion; I want them to be regarded, not swept away with the sands of time.

Generally, dream roles involve some significant level of perceived individual prowess that relatively few can boast about and where their input is valued (e.g. doctors, astronauts, athletes, etc.). But this is a main feature of archetypal egotism, whereby individuals chase their own prominence. Their excessive self-indulgence is typical of personality complexes—complexes, like narcissism, which are characterised by rampant selfishness, beliefs of being special, and only performing actions that lead to praise.

The affected frequently indulge their internal monologues to the points where they completely disregard everyone else’s. According to themselves, their views should trump all others and their perspective should be completely prioritised. Quite expectedly, they are outwardly self-centred as they become prone to listening to themselves and serving solely their own interest.

Eventually, unfettered self-indulgence begins to know no bounds as success conditions them further. Estranged from the real world, the shackles of consensus are released and individuals only rise to their own challenges. They are resistant to feedback and create motives where there weren’t any before. They begin to ooze sky-high confidence and become visionaries beyond their true capabilities. They seek only to gratify their egos.

Equipped with sizeable power they want more still. Drowned in ever-growing self-entitlement, their egos swell and recalculate what they seek. Ego is hungry once more. They won’t stop until they have assumed the role of our universe’s demiurge. Then what?

The prospect of more power: this is what they seek. But this urge is insatiable.

Power and the Deadly Sins

Abraham Ascher on Napoléon Bonaparte: 'There are also indications that the French emperor was affected by fits of megalomania … He spoke confidently of conquering Moscow and then marching on to India … [I]n 1807 he told his brother: "I can do anything now."' — Russia: A Short History, p. 89

Positions of power allow egotistical people to gratify their Sins. They can significantly influence other people; as such, they’re able to elicit pride, validation, delusion, stubbornness, and self-indulgence with big or popular decisions

The value of influence depends on the person who wields it. While someone might have good intentions, effects can be detrimental. But, worse, if their wish for individual power is overwhelmingly large, they will be less thoughtful of others. They carry a desire to be seen as ‘right’ at all costs and are willing to hurt or neglect people to prove it.

Such people just don’t know when to quit. For example, fraudsters Jordan Belfort, The Wolf of Wall Street, and Billy McFarland, whose Fyre Festival, logistically speaking, was always going to be utter disgrace, caused untold levels of damage with their scams, from unpaid wages to unmet dreams. The fact that their egos were big wasn’t the fundamental issue, though: it’s that they didn’t manage them and encouraged themselves to push for more when they didn’t financially need to. They were just not willing to accept defeat and created unobtainable goals until they were restrained from doing so.

An appalling lure to power is seen in politics too. Ideologies, systems of political ideas, reflect how we see the world; and, through them, egotistical politicians vehemently impose their ways of thinking onto others, undemocratically and manipulatively. Ideological crusades, for example, are simply recurring stories from history in which self-obsessed megalomaniacs have waged wars and committed genocides. They wish to conquer and invade and expand and spread their ideas. They made people suffer from their egotism and their movements.

Afflicted individuals carry no desire to relinquish power. Egotistical politicians manipulate, act autonomously, and execute undemocratic orders to coax their people into letting them stay in power for longer; sometimes they have to be forced out of power. Autocrats of all political hues cling on to power worldwide; it’s not an ‘underdeveloped-country’ problem. Many voting systems around the globe, such as the one in the UK, for instance, strangle opposition out of existence to serve the status quo and preserve centralised powers, where standing politicians act to perpetuate these systems—no doubt, because it benefits them too. Meanwhile, Ortega in Nicaragua, Erdoğan in Turkey, Putin in Russia, and leaders of countries beyond demonstrate how systemic perniciously selfish manifestations of politicians’ egos are in so-called democracies.

In the same political era we saw a dictator of a totalitarian regime and a celebrity-turned-president insult each other and argue over who had the biggest and most-powerful destructive nuclear weapon. Their egotistical tug risked mutually assured destruction. But, importantly to them, they were able to parade their individual power.

Elsewhere in the world notorious criminals, cult and religious leaders, media moguls, and self-appointed prophets are guilty of ego-driven delinquencies. Money sits at the centres of most endeavours but money is but mode of power: their delicate reputation is at stake. They are thus drawn to building empires; they yearn for a following; they want to be heard. They are self-styled shepherds amongst sheep. They are special and should be remembered.

People like Simon Cowell (pictured) and Rupert Murdoch are attracted to the prospect of great power in the media industry.

Pablo Escobar, a drug baron of the Medellín Cartel, is a pertinent example of a person who fiercely resonated with the idea that he, as an individual, should prevail over all; that he was entitled to be extremely powerful, regardless of the consequences.

On the back of an illegal drugs empire he made Forbes’ list of international billionaires seven years in a row and spent frivolously (including on his own zoo) and on buildings decorated with his own name like Trump’s. But, ultimately, his pursuits weren’t material. He fought to be untouchable such that no one was above him, neither the Colombian nor US governments. After his initial arrest he even built his own mansion-prison (‘La Catedral’) and operated it according to his own murderous rules and easily escaped a governmental siege. He intimidated others into appeasing him by granting him his self-styled right to power. He unleashed rage if his empire was threatened in any way, going as far as terrorising and killing civilians by ordering a commercial plane and Bogota’s security headquarters to be bombed. Escobar exuded ego. There was no mask. Nor was there any inhibition.

Similarly, Mexican gangster Joaquín 'El Chapo' Guzmán, previously head of Sinaloa Cartel, was also on a Forbes list. But money was only one key component of an umbrella motive: power. Guzmán met Sean Penn (pictured) before his arrest because he wanted Penn to direct a movie which celebrated the glamour of his life despite his abject living conditions at the time.

Power makes abuse more likely. From Weinstein in Hollywood to Ted Bundy, who was compelled to ‘totally possess’ his victims, people in positions of power exploit the weak by abusing them.

The people I’ve described think they’re above the law. They might think they’re great; in actuality, however, they’re behaviour is disgusting and rightfully maligned. There are ways to become successful without being totally immoral.

Taming the monster within

The egotistical people I’ve described in this article serve as extreme examples of egotism—they are proud, yearn for validation, are deluded, are stubborn, and know only boundless self-indulgence. But we, too, are naturally attracted to these things and should heed the warnings.

Self-importance can introduce more happiness to our lives if we let it. But there’s a scale. If we choose to seek unrealistic and highly favourable images of ourselves, we choose to let egotism override logic and compassion. We destroy cooperation and virtue. We sacrifice the happiness these concepts otherwise bring to our lives. Further, blinded by the lights of self-advancement, we might never be able to illuminate the paths that lead us to success in the first place. If a hunt for self-importance remains unhinged—left unchecked—our existential thirst for more will never be quenched.

So let us learn from these extremes to avoid their traps. Let us, instead, tame our egos by embracing introspection and proportionality to yield real results for ourselves and the world.