Ego III: How to Make a Genuine Difference

In the first article of this three-part series I discussed how ego is an inherent human trait—an integral part of human nature which fuels aspiration and drives us to succeed as individuals. In spite of this, if we are to believe popular opinion, ego is a stain on human existence. Through many of society’s teachings we are encouraged to exile ego from our psychologies as if it was a sin. I argue that this ring-fences us from potential happiness because it disregards our innate desires to feel important and denies us from rightly being proud of our achievements.

Peter Higgs, proud, cries as the Higgs boson, the particle he theorised in the 1960s, is here in 2012.

However, although feeling important instils happiness, the process of assigning importance to ourselves is subjective: how important we think we are to society is conceived in our own heads. Therein lies existential danger. Without some proof of how valuable we are to the world, we can be blinded to the fact we’re not actually making differences to people’s lives. We might be lying to ourselves about the changes we’re effecting, creating discomfort. We might even be doing damage to people when our egos spiral out of control.

Our egos beckon us to advance toward the kind of happiness that only personal accomplishment brings. But real fulfilment is rooted in living what we perceive to be authentic experiences; and we need evidence to believe that our roles in life’s play are genuine—built on our terms and free from external control but with feedback mechanisms from the world. To be sure that we’re enacting genuine changes, we must break down the barriers of uncertainty and find the truth of our aspirations for ourselves in the real world. To do this we must first tame our egos. Here’s how.

Ego's reach

Ego is what drives self-aware and self-concerned humans with their own personal identities to prevail as individuals. It provides a sense of self-importance and acts as a source of hunger, making us want to achieve on an individual level. It expresses itself as what we think our potentials are: a bigger ego demands greater achievements in our projects. This doesn’t have to be bad. Its fuel encourages us to take ownership of our lives and work towards seeing the fruits of our labour. It embodies a brooding desire to make change, to create, to innovate, to implement, to impart, and to be felt. It confers the urge to set ourselves apart from others through what we offer.

Ego’s existence also explains why we feel dissatisfied when we feel too capable—why simply operating under instruction—feeling like a cog—isn’t enough; why we envision altogether different futures when life becomes humdrum; and why we seek new challenges, progression, and personal evolution.

It’s why I think I can make a difference in my particular way—me and not anybody else.

'One Ring to rule them all'. Pictured: Isildur and the One Ring in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2002). The lure of power strikes the common weakness of Men in Middle-earth. For humans in the real world, too, the opportunity to feel important is enticing.

It also explains why we’re drawn to role models: the people we relate and look up to. What we’re actually doing, however, is escaping and visualising who we could have become through our heroes (though we’re fundamentally still rooting for ourselves). We feel their success, in real life and fiction, because they enable us to imagine what our accomplishments could be or could have been.

The simulated crew of USS Callister in Black Mirror S4E1 play out antagonist Robert Daly's fantasies. In this realm he is good.

The same relation applies between us and our children. We’re not only protecting the longevity of our genes when we hanker for their success: we’re projecting ourselves onto them.

Elon Musk inspires entrepreneurs around the globe: in unlocking his potential he unlocks theirs.

But however we formalise ‘success’, we get to define value within the frameworks of our worldviews: ‘I want to help improve peoples’ lives as a nurse’, ‘I am going to be a big deal on the Stock Market’, ‘I am going to be the best player at my football club’, ‘my business will flourish’ … We are pulled by the forces of our own self-importance toward the idea that we’ll be valuable to society in ways we can reason to ourselves.

World leaders relish the statuses they hold. The political power they wield and the influence they exert validates them. Other people validate themselves with different metrics of success, including but not limited to communally defined values such as wealth, academic accomplishment, and sporting prowess.

Mediation

Personal success is open to everyone. We set the goalposts according to the standards around us and our visions of ourselves. But we have to be realistic; else we fall prey to negative consequences. For one, untested and self-conceived notions of talent will fester if left to stew in our doubtful heads. This leads to insecurity—the kind that leads us to proclaiming we’re stable geniuses or professing we’re ‘like, really smart’.

If we forsake reason and proportionately to actively seek highly favourable representations of ourselves, we’ll inevitably end up miserable. Humbled and defeated, depleted and exasperated, we’ll be knocked back time and time again by unattainable yet self-imposed expectations. We’ll increasingly lose faith in the motivations we assembled!

Look at various social media services, which act as outlets for people to exaggerate, distort, and even sell ideas of themselves. On these platforms we rate each other through the number of artificial interactions recorded, even though these ‘encounters’ are remote and with distant people.

Instagram, for instance, is a hotbed of insecurity. Photos are exquisitely executed. Posts are contrived to be superficially perfect, which leads us to compare our lives ‘against unrealistic, largely curated, filtered and Photoshopped versions of reality’. What parts of us are actually being satisfied? And by whom are we being valued? The answers are sometimes troubling. We think we know who we are; yet we’re still willing to sell belied versions of perfection and give in to the pressures of idealised expectation.

Ingrid, played by Aubrey Plaza in Ingrid Goes West (2017), like many of us, has an unhealthy relationship with social media. Shouldn't we all be more honest with our self-conceived notions of talent, potential, and beauty on social media? Out of sync with the real world, lies foster brimming insecurity. Unravelled, such insecurity will reveal deep-seated unhappiness—anxiety, depression, and inability to stick to goals, to name but a few symptoms—because personal realities aren't met in real life.

By manufacturing idealistic ideas of ourselves we foster internal dissonances, wherein vast chasms open up between our imaginations and real-world experiences; where floods of unreliable opinions of ourselves surge through to sweep away the opportunities we could have otherwise learned from. If only we dreamed within the scope of a tangible reality, we’d be driving forward productively toward goals, avoiding pernicious self-destruction and yielding real-world progression, as we benefitted from interactions with people and our environments in meaningful ways because we genuinely made differences.

Haven’t you, yourself, felt the dismay of attempting to achieve lofty goals; felt them slip away, somehow further, the more desperately you wanted them? Conversely, haven’t you felt the contentment and pride from achieving goals that were within your reach, that were attained through hard work?

Bloated egos are blinding and even obstructive to the success we covet. We shouldn’t invest too much pride into being right: we should concern ourselves with finding means to reach the right answer by humbly approaching all tasks with curiosity and inquisitiveness. We should open our minds to new ideas, welcome new information, and learn from both criticism and praise. Being in touch with the real world is fruitful. We can still dream, take risks, and leave comfort behind as we reach out for success; we just need to measure our beliefs against something in the real world on regular bases.

While it’s important to dream, it’s auspicious to fulfilment of those dreams to ground ourselves in the real world first. Scrutinising results is better than time-consuming, self-centred persistence and false impressions do little for our happiness. In stark contrast, our lives are nourished when self-belief and the real world coalesce. We should, therefore, ask ourselves some provocative questions: Are my personal goals achievable and am I as successful as I think I am? Or am I delusional?

Validation is the teacher of us all

What is success if only we believe in it? A notion. A fabrication. A charade. We need some validation to actualise it.

Success unwitnessed isn’t enough to make us happy: we need to prove, externally to our minds, that our impact on the world is genuine. Only then is ego satisfied. With this proof in tow, when uncertainty shakes our self-belief and requires steadying, we can cling onto certitude.

To be fulfilled we have to see our visions be materialised. None of this is to say we can’t be aspirational—dream big—in the first instance; rather, we must, at some point, be able to prove the integrity of our claims. If we’re able to translate our fantasies into realities, no matter how mountainous our ambitions are, our pride cannot be judged as excessive to the point of impotent vanity.

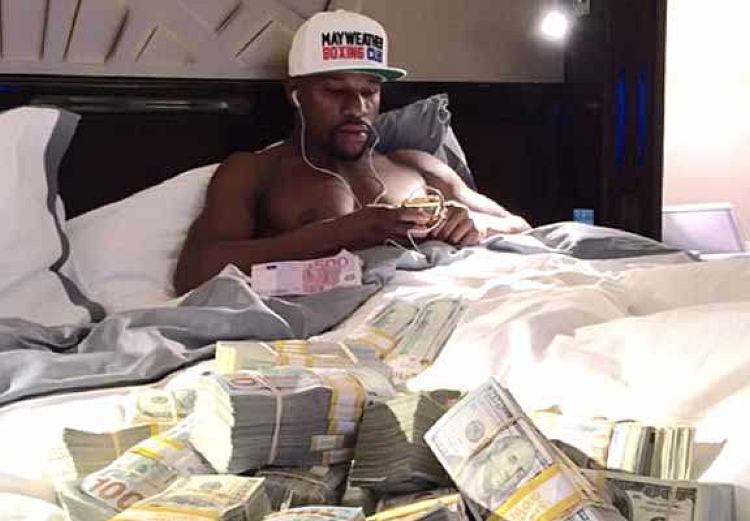

The American Dream: Floyd 'Money' Mayweather Jr. was boxing's first billionaire and one of the greatest pound-for-pound fighters of all time. The idea of being an elite boxer who accrued riches long provided him with a sense of self-worth. During his illustrious career he won 50 professional boxing fights, not losing a single one, winning world titles across five weight divisions and critical acclaim, entertaining millions in the process. Mayweather probably fantasised of being able to flaunt this status for most of his life. Although his immodest self-belief was vulgar, his belief in himself was justified because he was able to continually prove his worth, albeit probably at the cost of being a terrible human being.

Reality-matching amounts to graciously seeking validation in small doses to authenticate our potentials. Wait to see the lights of success before basking in them! And then we’ll know where we’re headed next.

But how can we tell what success looks like? Success is oftentimes shrouded in dishonesty: the fortuitousness of one’s circumstances is too frequently forgotten about and the chances of emulating them are incredibly slim. Still, the ones who preach to millions from their fortune-plated pulpits tell us that we’ll eventually ‘make it’ too if we work as hard as they did. But this is a flawed philosophy, for they don’t account for luck. They commit observer bias: we preferentially hear the success stories of public figures. Statistically speaking, only few are ever able to escape society’s net to replicate the likes of Lionel Messi, Rihanna, and Bill Gates in their quests for success. We can dream of being special, sure, but there’s usually a price. Ask the tens of thousands who apply to talent shows each year only to end up no closer to their goals. When it comes to dreaming big, the overwhelming majority of us are set to fail.

Abundant talent can be found in those who do succeed, of course, but it’s also frequently found in those who don’t. Life is unfair and society doesn’t always reward merit. I wouldn’t deny that Kanye West and Donald Trump, for example, were talented in multiple ways. But, instead of consuming their empty words, which are designed to praise their own dedication to their own causes, we need to be proactive in finding ways of practically increasing our own chances of success—that’s if we want to follow similarly upward paths.

At the other end of the spectrum

Validation is also a useful tool to undo self-depreciation and restore self-esteem. Where deficits exist we can use performance-based feedback mechanisms to learn about and reap greater satisfaction with ourselves.

Many people suffer with low self-esteem because they genuinely feel like they’re imposters. Despite evidence to the contrary, they struggle to accept their success. They do disservice to their own capabilities by underestimating themselves unfaithfully. Ultimately, they feel like they’ll be exposed as undeserving frauds if they enter themselves into arenas of aspiration.

I am one of these people. Studying for physics and master’s degrees, playing semi-professional football, being recruited onto a highly-competitive graduate scheme—I never felt like I belonged in any of these environments. Languishing, I was once my harshest critic. My ego wanted to bring about positive change but was perpetually dissatisfied with the scale of what I could do in the present.

But, by equipping myself with more objectivity, by reality-matching, I’ve been able to appreciate my achievements more and fixate less on what I could have achieved, whereby ‘success’ frustratingly felt like a forever-dangling carrot in front of me. I now take slower, steadier, and more-realistic steps towards more-attainable ambitions and remind myself of how far I’ve come.

What success really looks like

To know the true nature of success we need the systems we partake in, such as those in work and sports and politics, to confirm measurable impact (e.g. through positive feedback, number of victories, and popularity). While these markers can be misleading, we can still use them to measure our beliefs against. Plus, can we ever be content with our accomplishments without them? Arguably not because we’d have nothing to satisfy our egos with outside ourselves.

We require visibility: we depend on recognition as evidence to spur us forward productively. I bet Albert Einstein, would have been pissed off if he didn’t receive any accolades for his pioneering work in physics, which would have acted as some form of motivation. In the same vein, athletes and musicians relish the excitement of performing in front of and engaging thousands of fans and winning awards as assurances of their relevance.

But we mustn’t conflate evidence of success with popularity. Popularity is sold to us by a system that’s rigged. Further, to obsessively seek popularity for validation’s sake is to produce a hollow sense of achievement. By enlisting and entrusting the public, we give away our happiness at the behest of rotten values which impinge on self-worth. The idea of popularity also clashes with our desires to feel unique. To radiate mass appeal we are required to water down the essences of who we are. This carries a faux sense of acceptance because, by suppressing individuality, we are merely flogging personas. Recognition only begets fulfilment when public perceptions are moored to our self-reflections.

Lance Armstrong said he would choose to use performance-enhancing drugs again. To all those who have cheated systems for recognition: are they fulfilled? As ambitious people, they should lift the façade and ask themselves: What's more important: genuine, felt personal achievement; or a perception and celebration of it? How is the latter fulfilling? How do they live with falsity defining and overcasting who are?

We shouldn’t have to sacrifice who we are to become popular. We thrive on motivations which are born from serving our interests, not everybody else’s, and credentials are our own. How we make ends meet matters, for our own sakes, because success has to be really ours to be fulfilling. We must figure out what drives us and stubbornly pursue it to make our motivations reasonable and authentic whilst respecting the environments we release them into.

There’s nothing stopping us from putting forward the best versions of ourselves, hoping for them to be validated afterwards, while avoiding egotism. Ego should be embraced, not jettisoned: we can thrive knowing our values and dedication to them were felt by the world. But we have to take external factors on board in order to adapt and learn. We can convert ideas into our own and move them forward how we see fit but we can’t ignore the real world if we want our success to exist within its context.

Pictured: 'The Emperor's New Clothes'. Consensus needn't and mustn't be followed at all costs to be successful. If herds of people give you wrong impressions about yourself, you remain unvalidated and unfulfilled. Only a child was willing to give the emperor an earnest verdict on his new clothes in the story.

We must also question motivations which only serve unrewarding and overtly selfish interests. As humans, we don’t necessarily do something for nothing; however, we can enrich ourselves with the fulfilment of universal values. Can I connect myself to people? Does it improve someone else’s wellbeing somewhere? So we must objectify aims and lay them bare on the examining table to evaluate whether they’ll be helpful to society or not—otherwise we might just be advancing our own self-obsessed ideas for the sake of fleeting good feelings. Rationality will assist but not save us. Humans rocket-fuelled with ego, whose behaviours are aloof and unattached to people, don’t understand this still: they can always rationalise something for themselves. They believe in the righteousness of their convictions because they vehemently believe in their own superiority.

But we shouldn’t vilify ego-embracing individuals for being malignant in nature: such good-or-evil portrayals are unhelpful when it comes understanding why humans act the way they do. What defines the goodness or evilness of surgeons, CEOs, politicians, and pilots isn’t how individually ambitious they are: it’s what they want to achieve. Equally, unambitious people could be doing more to increase good and to decrease evil.

Donald Trump's agenda is himself: like a true populist (akin to Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson in the UK), he whips up storms and surfs the subsequent tsunamis for the advancement of his self. It is true that he achieved popularity but, we should ask, on the back of what? He is a money-obsessed, ostensibly-patriotic, misogynistic demagogue who regularly levels accusations of 'Fake News' when he's challenged. He panders to public insecurities (e.g. on racial tensions) to generate publicity, creating controversy which only leads to more discussions about him. He stands on the shoulders of inheritance. Ever happy to espouse falsehoods, he fills the void with post-fact information (e.g. to dismiss climate change). Does he really believe in his own words? Is he validating himself? Feeding his ego to remain on Centre Stage might achieve wealth and power; but, always wanting something more, is he fulfilled? (Win McNamee/Getty Images)

For these reasons we must call to mediation.

Finding the right balance for you

We are taught to steer clear of ego. As a concept we’ve moralised it and treated it as a wholly negative vice reserved for the conceited, who are worse off for embracing it. I argue that this is wrong.

First, it would be dishonest to deny ego’s innateness. We’re not senseless robots who operate as instructed without dissent. We possess complex inner psychological workings and we desire identity. An ego-less life is bereft of individuality and the character that belongs to it. We’d be husks without ego, unrecognisable shells of existences. The observable truth is this. We are proud and hungry individuals with purposes and convictions. Self-importance is more than a charm, something we lust for: it sits at the very heart of the human condition and we are all left unnourished by its omission.

Second, it’s unnecessarily limiting to defy ego’s influence. Self-importance fits within the remit of happiness because it promises to elevate self-esteem. As opportunities for accomplishment latently wait there, formless, we miss opportunities to be proud of ourselves. Ego feeds self-actualisation—growth of self—through the values we impart on the world.

How much should we dream? What can one human achieve? What does one human want to achieve? When are they fulfilled? These are good questions. The sky is the limit for some, whose big egos are insatiable: the thirst for more is never quenched and they are hungry but never full. We must question whether the perpetual desire to succeed and grow and succeed again is constructive to happiness. Although hunger can be happiness, like it is for me, there are so many more things to value in life which make us happy—family, health, companionship, community, harmony.

Fortunately, we can choose how much we allow ego to dictate matters. To become happier and securer in ourselves we can manage—sense-check—it to find the right balance. We can build ways of speaking productively to our egos—frameworks that mediate between self-importance and societal importance and seek validation to prove it and allow us to strive for what’s reasonably ambitious. We need to achieve mental symbioses between irrational ego and rational thought—between the dichotomy of internal fantasy and the external real world—to be at peace with ourselves. Divorce isn’t necessary.

Why embrace ego? We too often buy into aesthetic ways of thinking, where values are contrived, arbitrary, and unique to single cultures. Meaning is eroded when we peel away the veneer of social constructs to refine and examine what we believe in. One day everything will be pointless, futile, to an end. Nevertheless, we can extend happiness through honesty, pragmatism, and the subscription to more universal wellbeing, whatever our specific convictions are. Brimming beneath your surface is an ego, producing desire and intent; and along your way you might make yourself and others happier in a personally worthwhile pursuit.

So I say: don’t internalise ego to force self-importance to be associated with shame. Locate it; let it be your source of ambition. Find something you’re proud of. Revolt against lowly expectation; rise above mundanity! Acknowledge your talents and interests; find morality and purpose in them.

You have one precarious life: one opportunity to leave a profound and indelible mark on society. Embrace your ego; mediate it. You are ready to make genuine difference, to stand and feel your worth.

— John Keating, Dead Poets Society (1989)

— Zooey Glass, Franny and Zooey

'I'd like to add some beauty to life,' said Anne dreamily.

'I don't exactly want to make people KNOW more … though I know that IS the noblest ambition … but I'd love to make them have a pleasant time because of me … to have some little joy or happy thought that would never have existed if I hadn't been born.'

— Gilbert Blythe, Anne of Avonlea, The Anne of Green Gables Collection

— Samwise Gamgee, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002).