Life Without Religion

Featured image: Symbols of religious faith. (Rui Almeida/Getty Images)

My first doubts of God’s existence emerged because someone else always asserted that He (or She or They) existed in the first place. The notion of a Christian god was routinely proselytised to us at primary school, whose approach to religious education was hardly passive as we were made to pray and sing hymns. God, they claimed, can bring meaning to our lives, if we allow Him too, through Faith and the teachings of Jesus Christ, the saviour of humanity—a story that resonates with potentially over two billion people. Years later, having been too stubborn and inquisitive to be indoctrinated by my teachers and various other people, I seek to live a fulfilling life complete with morality and purpose in His absence. Only now, however, do I ask: how, exactly, is this possible when, frankly, I think there is no point to my existence?

Atheism

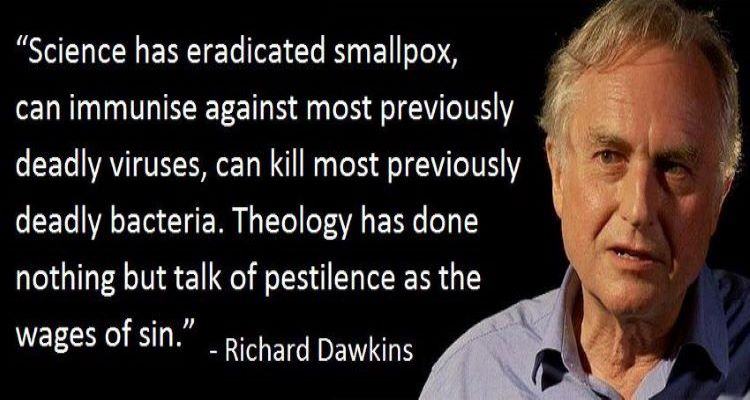

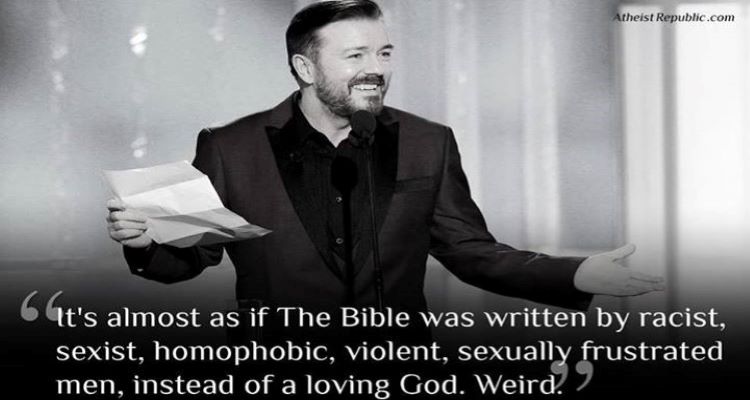

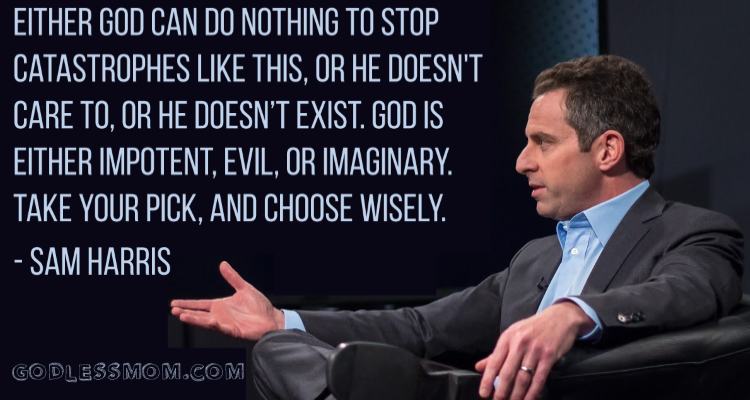

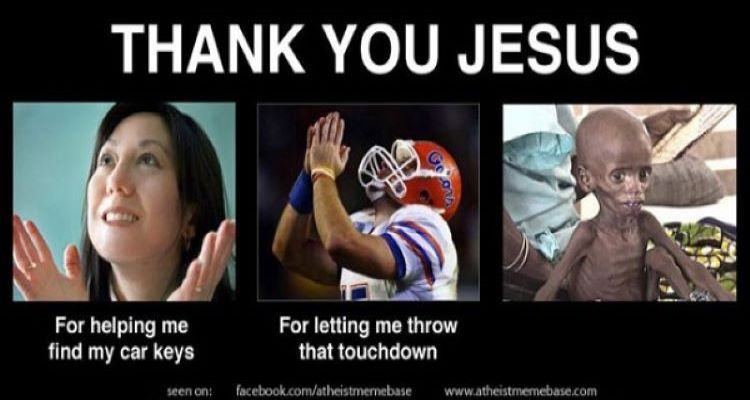

Atheism seems to suffer from an unfavourable image. Labels such as ‘rampant’ or ‘militant’ are flung about to describe atheists’ approaches to debate. Prominent and outspoken atheists, such as Richard Dawkins, Ricky Gervais, and Sam Harris, are particularly strident in debate. Arguably, they’ve done themselves and their atheist movement no favours as they’ve attracted negative media attention and inspired hordes of keyboard warriors to perpetuate their attitudes.

Personally, I agree with what these people say a lot of the time. Nonetheless, in the eyes of many, they send out a negative message. This is a problem for me. Admissions of my own beliefs—or lack thereof—have to be conveyed gingerly since I fear that I may somehow contribute to this negative stereotype. Atheists are unnecessarily angry, obsessed, scathing, and self-righteous, so they say. Why do they care?

Perhaps the zeal displayed by these forthright atheists reflects a growing eagerness to explore the benefits of a god-free lifestyle against a backdrop of underrepresentation.

In the UK around 50 % of the population doesn’t affiliate themselves with a religion (British Social Attitudes 28, 2010; The Guardian, 2016)—the most popular affiliation of any group—and this number is expected to grow. Yet the prime minister declared the UK a ‘Christian country’ in the face of its plurality on numerous occasions. Moreover, under his guidance he enabled schools not to give parity to non-religious interpretations of the world in religious studies. The next prime minister, a vicar’s daughter, planned to abolish admission caps in religious schools and approved more religious free schools, further promoting ways to divide us. Additionally, our unelected head of state is the Supreme Governor of the Church of England (CoE); CoE bishops hold automatic rights to sit in the House of Lords (the UK is the only Western democracy to legislate this); and since the recreation of the Secretary of State for Education post in 2010 all three holders have been Christian: Michael Gove (CoE), Nicky Morgan (‘Christianity’), and Justine Greening (Anglicanism if her Wikipedia page is anything to go by).

Justine Greening.

Despite this there is growth in non-belief, which may be attributed to a number of factors. Greater access to education, growth of resources on various platforms housed on the Internet, and increased diversity have all opened our minds to more possibilities, whilst scientific discoveries continue to challenge religious claims. Meanwhile, religion can inspire unethical acts—Jihad, terrorism born from the rise of groups such as Islamic State, and other dangerous manifestations of fundamentalism—causing us to feel ethically detached from faith. Furthermore, there is often disillusionment with religious establishments: the Catholic Church, for example, may have come a long way since endorsing the Spanish Inquisitions and the Galileo affair but topical issues such as sexual abuse of children under its own roof and its systematic cover-up have damaged its integrity.

Galileo before the Holy Office, Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury. The Roman Catholic Inquisition condemned and indefinitely imprisoned Galileo Galilei in the 17th century for being 'vehemently suspect of heresy' for his scientific support of heliocentrism, which contradicted the belief that Earth was located at the centre of the Universe. Such hostility and persecution is no longer rife, fortunately.

Ultimately, more and more people are finding the stories written in religious scripture too unbelievable. Moreover, unleashed from dogma and more enlightened, many suppose that the correlation between religiousness and morality is dubious. Still, given the worldwide prevalence of a belief in a god, there must be a strong appeal of the religious way of life. Clearly, there are many good and happy religious people.

But there’s an alternative for those who seek a similarly fulfilling life. If we unshackle ourselves from God’s will, life doesn’t have to be empty. In this alternative life we can hold ourselves accountable to our actions and be more critical of ourselves, allowing ourselves to be freer.

Humanism

Humanism is a philosophy I wholeheartedly support. Its definition and application may be fluid but the guiding principles remain the same: seek to improve human wellbeing through reason; consider individuality and social cooperation equal; and be uncertain, apply scrutiny, support intellect, rely on evidence. There’s no god who obliges you to wear certain clothes or suppress your sexuality. Every stance is centred on collective wellbeing, giving us an uncriticisable moral focus, which, if we adopt, gives us purpose to our actions. (My only qualm, actually, is that equal consideration of other species isn’t accounted for.)

Conceivably, many of us are humanists without recognising it.

Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man is a symbol of humanism: it embodies the cultural and intellectual growth of the Renaissance.

Like atheism, humanism doesn’t necessitate a god, rejects a religious framework, and stipulates that we only have one chance at life. However, not all humanists are atheists (and vice versa). Nevertheless, an atheist who reasons that we are responsible for our own actions and their consequences and who cares about the welfare of other humans is probably a humanist.

To demonstrate humanism’s application, consider a topical human issue: assisted suicide, genetic engineering, prisoners’ rights, cloning, or the hypothetical choice of giving birth to a severely disabled child. Let’s take the genetic engineering example.

Embryos, let’s say, are experimentally modified and disposed to help us understand the development of a severe and fatal condition that develops in adolescence. There’s a plethora of philosophical questions to ponder that religious doctrine is simply to black and white about. Humanism can guide us. With human welfare at its centre, we are equipped to ask good questions that may have answers: Does an embryo have rights? What’s its capacity to suffer? Can this be quantified? Does the embryo deserve a shot at life, as a human? Who stands to benefit in the short- and the long-term? What’s the cost and what could have we spent resources on instead? What’s the risk?

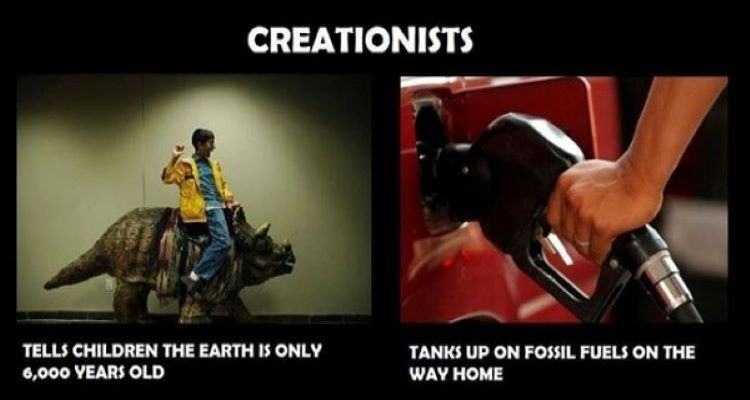

A religious person can consider all of these questions, too, but they are limited. Their ethical framework is rigid: it’s married to what ministers of their particular religious branch or sect says. Furthermore, what these ministers say is statically rooted in sacred text: while the rest of us, in time, learn and society changes swiftly in response, untouchable text is a constant source of a river of unverifiable information. Approaches to moral questions can, therefore, be dogmatic. Such dogma is underpinned by investments in unbelievable claims about a god’s existence and events that happened. Believers are asked to have faith that these claims are true. While an individual can interpret religious content how they want, this, if anything, represents a movement away from a religious framework.

Religious believers, then, lose rational autonomy because they are constrained by their faith-born belief systems, which tell them, almost explicitly, what to value. Even if they adopt reason, they will find it difficult to navigate moral through moral dilemmas in ways which are compatible with their spiritual beliefs, for religiously swayed interpretations are centred on these spiritual beliefs, not fundamental aims to improve quality of life for fellow humans. While they might argue that the two are associated, in modern times believers have been regularly exposed as prone to intolerance. They might try to offload the burden of ultimate responsibility to a god by presupposing that their word is final. However, this constitutes a reasoned choice to restrain their own ethical framework: a wilful removal of one’s own freedoms. Accordingly, we can hold them to account for their backwards views since they removed their own avenues of arguments. Personally, I just wouldn’t want to live like that—my mind constantly being held back.

A personal perspective

From an early age my inherent scepticism and curiosity was apparent from my incessant questioning of everything, according to my mother: teachers at my primary school were always going to struggle to convert me. To the contrary, their attempts to do so fostered a sense of resentment within me. I departed a religious perspective to adopt a humanistic outlook which has always been positive in the sense I often see potential to be good in things and people.

While I’ve always been inquisitive, I can also attribute my views to the long education I’ve received and the cognitive evolution it stimulated, my growing maturity, and the experiences of new places and cultures I’ve gained. I recognise the benefits of a religious life—the communities of music and sport are my churches—but I see too many difficulties that are incompatible with my own worldview. Maybe this is also true for you. It wasn’t for me.

The whole process of developing my views was emancipating: it cleared and opened my mind and allowed me to flourish with my outlook on the world and my place within it. I feel responsible and accountable for my actions. Veganism has been liberating, for instance, and by further accepting how my actions may affect future humans I feel more protective over the environment. Moreover, I can’t stand by social injustice. Politically, I feel more confident of my convictions since they are founded on reason, evidence, and experience—things I can corroborate with data and experiences in the real world. Faith assures me of nothing; it’s a blindfold. Humanism, on the other hand, gives me morality and purpose.

Sea Ice Remnant Svalbard, 17th July 2008. Our decisions now affect future generations. (Camille Seaman)

The foundations of my ethical framework are compassion, equality, and social cooperation. I feel satisfied when I benefit others, which further encourages me to be kind, understanding, and charitable—virtues of my non-religious life that instil purpose in me.

Given what I’ve come to value in my life, I conceive of ways to try to benefit society with my values hand in hand in ways that are in total harmony with reason. I’m not pretending to be a great person; however, if I think I ought to do something, my approach to something will reflect this method. I work in the NHS, for example, to innovate our public health service and I judge the quality of my work on how well it serves patient outcomes. ‘Value’ is a dynamic term, though: your own attributes and passions may render your interpretation different. ‘Value’ could mean educating or protecting people or making them laugh or feel inspired. However you reason your dedication to other people, you will be doing at least some ‘good’ somewhere, so long as you have sanity and rationality by your side. Dogma just makes goodness more unlikely to be obtained.

Helping each other.

I have purpose. More profoundly, though, I can sense awe and wonder without a god. I became a physicist to help me understand the universe—the birth of stars, space and time, the fate of the universe—and ponder life’s biggest question. This fills me with a deeper sense of purpose.

In conclusion

Humanism doesn’t dictate how you should live your life. It can, however, guide you toward moral behaviour whilst you live a life defined by your own values. If you’re prepared to embrace it, it’s simple: care for the welfare of others and invigorate this goal with reason. You may just find happiness and fulfilment and freedom through your purpose in return.