Post-Fact Politics: Why the Truth Should Govern Us

Featured image: Donald Trump, the President of the United States.

Facts empower us to make objective decisions for our own good: for society and for ourselves. However, facts aren’t always available to us nor are they always easy to understand. Nonetheless, as self-important humans, we often hold unequivocal beliefs on magnificently complicated things, be it the economy, justice, foreign policy, or even the cause of our own existence. Although this is our prerogative, in a period of great political flux and division, from referendums and elections to acts of terrorism, is it appropriate to hold factually deficient opinions on topics that matter to us all?

Fact versus belief

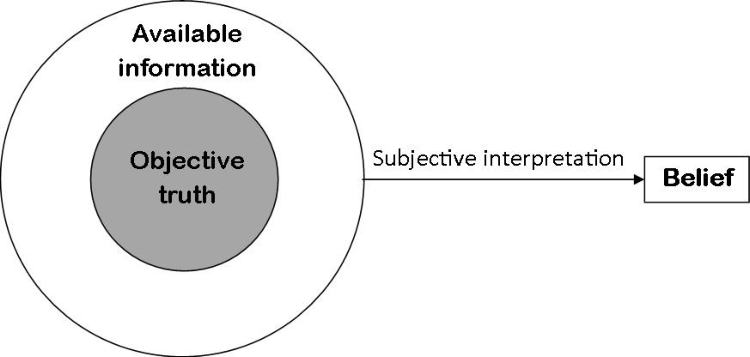

To begin with, we must appreciate how our brains operate when they are tasked with forming beliefs. At the core of any topic we there could an underlying objective truth. While philosophers, especially of the sceptic kind, will deny that there can be facts like this, let us presuppose there can be for the sake of understanding how we form beliefs about them. The objective truth, for example, could be the socially optimal method of taxation and government spending or the best nuclear weapons policy for protecting people in a particular country. Clearly, there is no overwhelming consensus on either. We can attempt to turn our beliefs into truths (facts) through some process of justification but we’re never quite there.

Collectively, we come together to try to understand the true nature of problems—in academia, industry, charities, and more—through education and research. But, given the finite resources of any one project, objectivity is hard to come by. Meanwhile, the public still ignores advice or simply disagrees with it in favour of another set of proclaimed truths.

Factual beliefs are even more evasive to someone alone. One person possesses fewer resources than a body of people armed with ad hoc resources tailored to collect and sieve through relevant data. Yet it’s the former who have to be politically pandered to. With limited time, they only scrutinise problems so much, while their incumbent worldview is probably already biased, which limits their impartiality and means they frequently prioritise truths that matter to them. ‘Facts’, then, are often landed on in virtue of some personal faith and what we each believe isn’t necessarily a faithful representation of reality.

The relationship between truth and belief isn't direct. Subsequently, nor is belief always faithful to truth.

As intelligent beings we’re also able to draw our own subjective truths: we project our minds contents onto the world. This in contrast to computers that cannot consciously think for themselves and probably simple-minded animals, which have limited intelligence and simple brains that one-dimensionally interact with their environments. Subjectivity can be beautiful. Our own interpretations of the world enable us to be creative and unique—be individuals. It also facilitates healthy debate in terms of constructive disagreement in cases where problems have no clear answers. However, it does legislate a divorce between belief and truth, so to speak.

We're not omniscient.

Why is all of this important? Well, without being objectified, say, through rationality or evidence, beliefs are relegated to being opinions; and even though there will always be a variance of opinions on a matter, there could only be one set of truths that bear relations to outcomes of decisions.

This is all particularly pertinent to topics that people find complex. The waters of belief formation are muddier when we try to understand nuanced topics. This isn’t our fault: there are simply things out there that most people can’t even begin to comprehend (e.g. with regard to economics, law, and environmental science); and the more difficult the fact is to obtain, the more we lose sight of truth because we can’t fathom it for ourselves, individually and as a collective. This paves the way for human irrationality to have an increasing influence on policy-making, for the feelings we have around certain topics are still real and can be exploited unlike the actual truth.

Irrationality

If we command no understanding of a topic, our opinions will be shaped without the aid of truth. Furthermore, we may be the most intelligent beings in the Universe but we’re still humans who share characteristics with our ancestors. We have been programmed by nature; predisposed to be fearful, loyal, proud, untrusting, and so forth. Feelings, therefore, can override the desire to decipher facts through reason.

Someone who is greatly patriotic, for example, may put Britain’s interests way ahead of others’ despite the many things we have in common with all humans of all colours and creeds. This isn’t to say that feeling a sense of loyalty to your country is necessarily a bad thing: it can unite people in times of adversity, whilst national pride can improve peoples’ welfare. Nor is it an exclusive feature of those lacking intelligence. Far from it. Nevertheless, outright patriotism is irrational and doesn’t require factual information to manifest, even though facts are often essential to determining optimal outcomes for people and society.

God save our Queen.

The real truth of a matter, then, can be immaterial with respect to belief. Fair enough. But it’s this that allows the spread of information to be perverted, for beliefs can be swayed; facts can’t. Hence a new kind of truth has prevailed: the truth we want to hear.

Feeding you what you want to hear

There are many ways to deliver truths which people are more prone to believe; and modern society has become well-equipped to distribute information to them—information which suits dominant attitudes and creates ripe conditions for the post-fact wildfires we see today.

The so-called echo chamber is one such conveyor, whereby we confine ourselves to spaces where our own ideas are espoused and repeated.

Many of these spaces are proliferating in the digital world: social media algorithms personalise information for us and we, as users, can selectively tailor our own feeds. Echo chambers are present away from the Internet too. For instance, networks of relatively socially and racially uniform friendship groups can feed into each other’s narratives. The result is the same: as diversity dwindles within our own fragmented communities, the tendency is to become more harmonious and conform. Vacuums of independent thinking thus emerge and platforms for unchecked, supposed truths are bred. Views that conflict with common opinions are deemed false and censored from the consensus.

The echo chamber. (Christophe Vorlet)

This situation is compounded by other modes of selective information distribution: fake news is written to peddle favoured agendas; opinions exude hyperbole to gain traction, when the truth is probably duller; memes, which are reductionist by nature, are read and shared; and unreferenced articles are automatically trusted. Consider a contentious topic such as the role of Islam in society. One can easily find both positive and negative ‘news’ stories. Ask yourself why there’s an absence of truthful information reported in each case. More innocuously, even users of social media will contrive stories to gain traction.

It’s easier to adopt a default stance and fit our news around it. As such, people cherry-pick information from a multitude of sources to align it with their beliefs. Requisites to forming a proportionate, informed, and balanced view, such as a review of available statistics, are forsaken in favour of a pre-determined agenda.

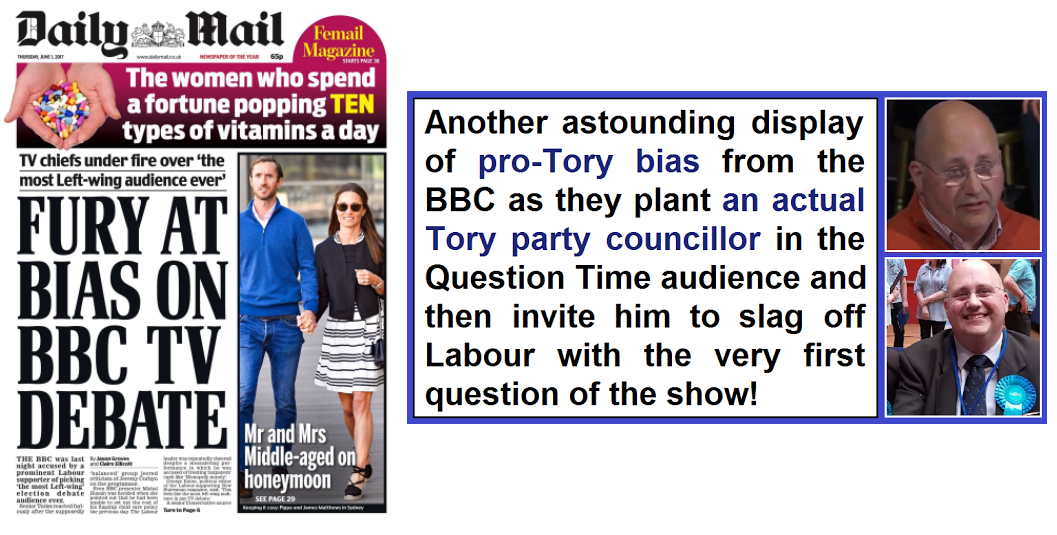

This assertion is substantiated by arguments over the political bias of the BBC even though evidence indicates that there’s more partiality towards one end of the political spectrum than the other.

Bias of 'The Beeb': Does the BBC exhibit left- or right-wing partiality? The Daily Mail (left), who generally oppose funding to the BBC, and independent blogger Thomas G. Clark (Another Angry Voice; right), who is anti-Tory, will tell us different stories. In another example, the Telegraph attacked the BBC for its most recent episode of Question Time; left-wing group Occupy London then responded by labelling their protest 'a load of typical Tory shite of crying wolf'.

Language can be nuanced to make a topic more persuasive too. This can be achieved literally, with words such as ‘reform’ instead of privatisation (or is that my bias manifesting there?), and metaphorically. Additionally, since there’s an inherent challenge to rendering genuinely complex material more digestible, content is simplified at the cost of accuracy. This often is why one variable relating to a problem is discussed at a time when there are usually many more, ignoring the issue’s intricacies.

Truth is clearly becoming less valuable in comparison to appeal. Unfortunately, wanting to believe something doesn’t make it any truer; it makes us more impressionable. An expression of belief or a fanciful statement might resonate with us but it means very little without facts to back up the claim. We must then ask: whose interests are we serving when we consume information we don’t fully analyse and understand?

Manipulation

The truths we want to believe may indeed make us happy. But if we want to believe something, we become more susceptible to persuasion—especially if the topic caused us to be emotionally charged already.

Even if one is politically impartial it’s difficult to see how Boris Johnson MP, a man who clearly sought to be Prime Minister one day, didn’t opportunistically conflate widespread sentiments against the Establishment with patriotism to campaign for Brexit for his own political vantage. The Treasury, meanwhile, was accused of implementing Project Fear to push for the United Kingdom to remain. Feelings can be targeted: ‘facts’ are malleable.

The Brexit battle bus. Sometimes we're trusted to vote in referendums despite true complexities being reduced to a binary 'Yes' or 'No'.

One has to question whose hand we’re feeding on information from and what influence they intend to impose. It may be purported that news stories are factually complete to support their worldview when, actually, their intention is to purvey their favoured ideologies. Even if they truly believe their worldview supports the idea of the greater good, this is a disservice to the truth.

Moreover, if there’s an incentive for them to gain something outside of our interests, should we be surprised if the notion of truth is perverted? With politicians close to small groups of people with vast amounts of power—for example, in business and in media—it’s easy to envisage how such influence can be exerted.

We should be insulted by these groups of people who seek to exploit us. A pertinent BBC documentary, The Century of the Self (2002), analyses this in detail. This critically acclaimed, four-part series digs deep into the implementation of Freud’s theories in society: the view that human beings are selfish, instinct-driven individuals and how this can be manipulated for the gain of the manipulator.

Political leaders, such as Ronald Reagan and Margret Thatcher, have mercilessly employed similar tactics to install their inward-looking visions. Today many politicians, too, treat millions of us as if we’re dumb for their own political gain.

Similarly, big business has historically attempted to extinguish our capacity to think independently by playing to our irrational desires—by profiteering from nicotine addiction, by exploiting our instinctive appetite for sugar, by pandering to our desire for the scarce and the romantic, and by causing body-conscious men to obsess over protein. The list is non-exhaustive.

The less we think, the more we become ideal consumers and political fodder. Hopefully, though, there’s capacity for positive change.

Today's political environment

Many people in today’s society feel disenchanted from politics—because they feel ignored, because they feel poorly represented in terms of massive underrepresentation in Parliament, because of expenses scandals, because of the pay rises against a backdrop of austerity. We hear that ‘they’re all the same’; that ‘they’re in it for themselves’.

A fightback may be on the cards. Populism, politics for the disregarded, has grown significantly. But is there any substance (truth) to their claims? Or, at least, is there any coherence in their arguments such that we can begin an attempt to ascertain truth their claims (e.g. that freedom-of-movement immigration is bad news for poor people)?

It’s fuzzy and lacks a unified ideology which seeks to exclusively represent ‘the people’ and is against a corrupt elite. From the ideologies of Podemos to those of Donald J. Trump, they pose easy solutions to complicated problems, whilst experts are shunned. Even Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders have been implicated in engineering popular emotions and perceptions. It has become the disjointed yet collective voice of the disillusioned by promising them the world.

With such an amorphous and ambitious political foundation can populism practically deliver anything meaningful? Will it seek the truth or just pander to sentiment? Do the supposed spokespersons of this form of simplified politics really work for the best interests of the people they represent? Or are they in it for themselves and their friends?

'The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive.' — Donald J. Trump, Twitter, 6th November 2012.

This way of doing politics has presented itself to us during a precarious period. The volatility of politics around the world today is palpable. Brexit, the rise of Donald Trump, and the United Kingdom’s general election have demonstrated this, creating simmering unpredictability. Change, finally, feels tangible. Is this good? Is this bad? Well, change from a stale status quo can only be good; but, with the added pressure of grand populist promises, what is more difficult to determine is how we achieve realistic results that are objectively better for everyone.

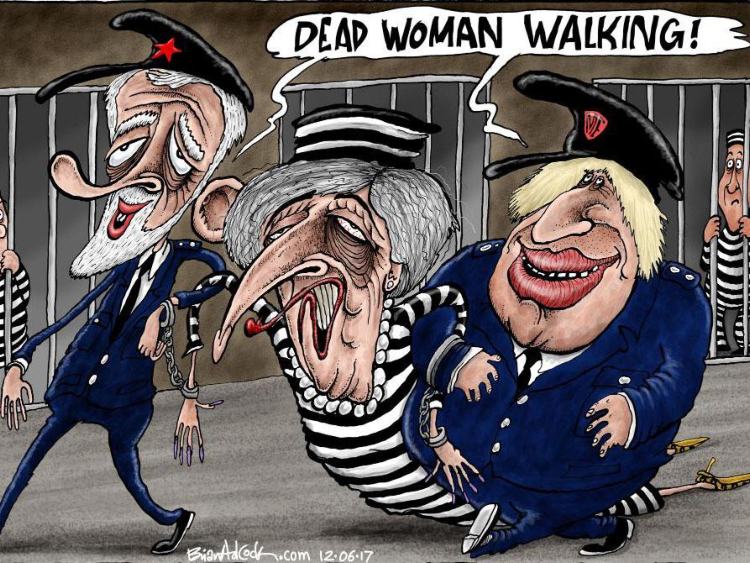

Theresa May being dragged away by Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn — Brian Adcock/The Independent. The political hand of the Tory party in the United Kingdom was debilitated following the general election on Thursday 8th June 2017.

With all of this in mind, we must grasp change with the right tools. After all, by virtue of democracy we, theoretically, speak for ourselves.

Building solutions

Life’s landscape is full of unavoidable gulfs between complex fact and understanding. Complexity is politically romantic: it obscures facts and is conducive to fact-deprived rhetoric. On such matters we should be careful when forming our opinions since we cannot say that we protect our own interests if we don’t understand them. In times of despair you may wish for life’s events to be simpler but, in fact, your interests are best protected when you’re empowered with accurate information and not amenable to your irrationalities.

Disillusionment exacerbates the issue, for we become less attracted to facts and more susceptible to persuasion. A form of simplified politics with big promises has intensified. The objectivity necessary for the achieving optimum outcomes is distant.

But not all are obstacles to knowledge empowerment are immovable. We can identify bias and challenge the misreported. The reality, however, is challenging. As Nick Cohen reflected, ‘You will still be able to see it if you peer hard into the darkness. But you will only find it if you want to look for it, and the lesson of our times is that the majority of our fellow citizens do not’.

Given the inherent complexities of life and prevalent indifference to change outside our own personal challenges, I worry that only the elite can truly sustain themselves. But events that impact us all mustn’t go unexamined.

'The unexamined life is not worth living.' — Socrates.

For those who want it, we can first defend ourselves by proactively seeking the truth, which will act as a foundation for change and will energise the apathetic. As we fly forward through the 21st century, traversing the Information Age, the potential for scrutiny has never been greater. But the onus is on us to pursue objective truths—particularly when opinion is divided and other people will be affected. In it we can find comfort in being governed and protected by knowledge, not by opportunists and demagogues who only look to promote themselves.

So start off sceptical. Be prepared to eschew sentiment. Rigorously assess your willingness to believe something. Fact-check and proportionately interpret information from a range of sources. Immerse yourself in the full depth of a topic if the complexity requires it.

Stand up for yourself. The examined life is worth striving for.