The Philosophy of Sartre: A Mystery in Broad Daylight

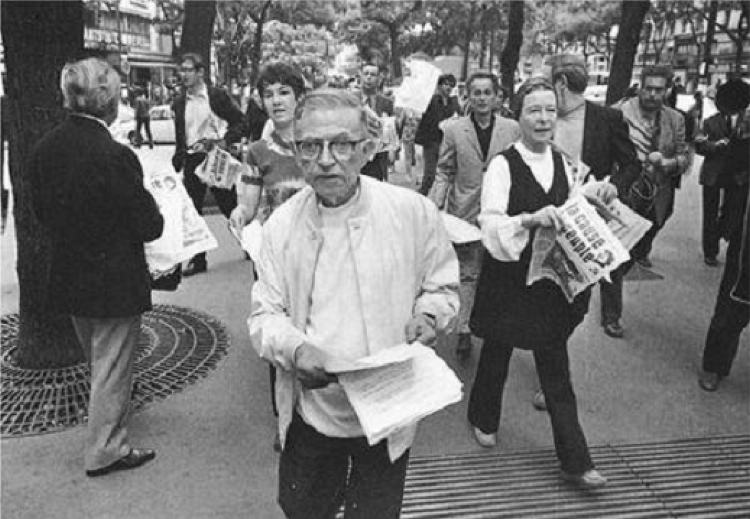

Featured image: Only two people have declined a Nobel Prize. The first was Jean-Paul Sartre (pictured), who refused the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964 because a 'writer should not allow himself to be turned into an institution'.

B

orn ‘Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre’ on June 21, 1905, and known to his lover and partner Simone de Beauvoir as her ‘dear little being’, Sartre became a variety of different things to the world: a prisoner of war, a journalist, a playwright, a novelist, biographer, a Nobel Prize winner, and, most famously, a philosopher.

However, there is a word to describe a man like Sartre, who was many things and yet still ambiguous, a word used in the Ancient Greek poems of Homer to describe the Greek anti-hero Odysseus: that word is ‘polytropos’, which literally means, ‘turns in many ways’. This description is befitting of Sartre, whose life had many twists and turns and many different forms.

But today, as we reflect on Sartre’s life, we should be encouraged to do his work much greater justice than it has been given in the past. So here I would like to do Sartre a due favour by clearing it up. My hope is that, upon finishing this article, you will realise that while Sartre’s philosophy is almost always incurably misunderstood, he possessed an incredibly brilliant mind; and now is the time to heed it.

Misunderstood

A young Jean-Paul Sartre.

One of the most recognised events of the life of Sartre occurred during his famous lecture ‘Existentialism is a Humanism’ on October 29, 1945, at the Club Maintenant. In this lecture, through which he sought to defend his existentialism and correct common misconceptions about it, he declared the following:

The published text of Sartre’s lecture quickly became one of the bibles of existentialism, so to speak, and made Sartre an international celebrity.

Sartre, however, quite openly regretted giving the lecture and continued to regret it for the rest of his life. Not too long after giving it, he said:

The lecture, quite ironically, allowed his philosophy to become a caricature of misconceptions, representing the faded dreams of his ambitious philosophical system.

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, partners in philosophy and in love, enjoy a hot beverage.

This is perhaps the most-consumable and most-concise work he produced in his lifetime. It helped promulgate his philosophy far and wide. Such a feat would strike pride in many authors. But this is Jean-Paul Sartre: the first writer to turn down a Nobel Prize in Literature for fear of ‘being turned into an institution’. It was his theories he wanted to be heard—and faithfully understood at that.

Were Sartre alive today, then, with his popularity still evident, he would perhaps despair at how his philosophy now belongs to a vast territory of memes, wherein he is little more than a pipe-smoking, amphetamine-consuming, cross-eyed philosopher who was only capable of crafting popular philosophical soundbites about the meaning of life.

Sartre’s philosophy deserves so much more than this.

The proclivity in which misconceptions about Sartre have infiltrated not only common minds but academic minds is so great that, in the English translation of Jean Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, Hazel E. Barnes had to begin her introduction by discussing the mangled form Sartre’s work took in the general public. She put this down to critics not seeing Sartre’s works as a ‘total system’ of philosophy:

In this article, I hope I can decouple Sartre’s philosophy from popular misconceptions of it. It’s certainly due this treatment.

I hereafter focus on two of his most-prominent concepts: radical freedom and bad faith.

On radical freedom

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir protest together. Somewhat confusingly, Sartre claimed he never accepted any particular power over him—that he was a 'traveller without a ticket'—despite being an anarchist, Marxist, and cultural revolutionist. He believed that all societies were best understood as arenas of struggle between powerful and powerless groups, where to oppress another is to attempt to validate one's sense of self by denying their freedom—something, in whatever the context, he vehemently opposed.

Sartre’s theory of ‘radical freedom’ features heavily in almost all of his philosophical works. There is a dizzying array of quotes for us to cite which reveal his near-obsession with the concept, the most famous of which, from Being and Nothingness, is the hyperbolic:

What does this actually mean?

Freedom, according to Sartre, is born in anxiety: an anxiety which informs ‘man’ which choices he can make. But man is condemned to be free, he expands, because he ‘did not create himself … and from the moment that he is thrown into this world he is responsible for everything he does’ without choice. Such freedom is nauseating if man acknowledges ‘pure’ facts: that his consciousness contradicts his body’s finitude; that possibilities outnumber his reality. Radical freedom is frightening and it’s easy for man to run from it—for example, to the safety of bourgeois roles, in which he can believe his high social standing gives him a ‘right’ to exist as he is.

Thus the basis of radical freedom is ontological in nature: with reflective consciousness, man is free, through his fluid and purposive ‘for-itself’, to transcend the regular pre-reflective stuff of the ‘in-itself’ that makes him; and this ambiguity scares him. Indeed, we are all beings ‘in a situation’.

Through Sartre’s existential ethics, we are told that we should value freedom and the freedom of others, else we may all fall into the traps of oppression. Hence Sartre’s notion of freedom is multifaceted, spanning phenomenology and politics in relevance. Yet when people come across Sartre’s notion of freedom they take for granted what it means to be free: they do not see a word or concept with ontological beginnings that underpins faith and choice, but a mirror to what they believe freedom is—which is usually a very simple notion of free will. Anyone who has read, at the very least, Being and Nothingness will read a completely different philosophy.

In Being and Nothingness, the phrase ‘free will’ appears only four times. In each instance, he does not support the concept of free will; he criticises it. Free will and determinism are discussed together as part of a debate that Sartre finds mistaken. He writes:

To Sartre, there is freedom and there is a will. One can will their freedom, but freedom is not a product of will. Freedom, Sartre claims, is ontologically constituted in our ability to consciously transcend the material situation and is a product of our imagination. It is not based in metaphysical causation. Nor does it emerge from its material cause-and-effect processes; rather it is found in autonomous choices with respect to them.

Whether choices are ultimately caused by something else has no bearing on freedom. Through the self-awareness and reflection of the for-itself, we consciously make choices above the in-itself, where the former is an ‘other’, non-identical state that temporarily removes and ‘nihilates’ the latter. (Granted, Sartre’s freedom can be criticised for being somewhat arbitrary without real criteria.)

Sartre has been condemned, too, but not by his freedom but in his wilful blindness of the Gulag and Mao.

However, freedom, as Sartre says, is ‘nothingness’, which haunts us because freedom is totally subjective. To act with complete freedom is to be a ghost, something which he explores through the characters in his fictional work The Chips Are Down, in which Sartre reveals that in every act of freedom comes a residue of unfreedom that eventually overtakes it, an unfreedom that grounds our freedom and permeates. I can choose to eat coal, but the bad taste, the breaking of teeth, and the inedibility will eventually limit me.

Therefore, Sartre’s idea of freedom is not some odd, dreamy call to a playful kind of freedom, but rather a terrifying notion which dwells within unfreedom. Such freedom, Sartre argues, arises with ‘vertigo of responsibility’ and ‘negative ecstasy’, for the agent now realises the choices they are responsible for; and it is not the fall from a height they fear but the power to choose. Duly, many people lie to themselves about what they can or can’t do to avoid that anxiety.

If one chooses to immaterialise their material situation, however, they can buffer oppression: with responsibility of everything that happens to themselves, they will embrace radical freedom.

This idea brings us to the second of Sartre’s two infamous ideas: bad faith.

On bad faith

In 1960 Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir visited Cuba, where they met with Che Guevara and toured the island with Fidel Castro, to report on the ongoing revolution. Sartre's disposition towards Marxism and distaste for oppression led him to support and condemn the revolution and the regime in equal measure. (Photo colourised by Colorem)

An attempt to renounce freedom and responsibility, however, is also a choice. ‘Bad faith’ is the concept which Sartre uses to describe this relationship.

Bad faith is, perhaps, the most-well-known concept of Sartrean theory, for it digs deep into the nature of our personal choices. It is the denying oneself of choices and the adoption of false values, which prohibits the free and conscious for-itself from escaping the cause-and-effect in-itself.

Bad faith, then, is an appeal to determinism. Consider the following examples, in which bad faith is demonstrated by the subject, in order to get a feel of the concept:

- An older woman believes in astrology; astrological signs tell her who she is now and what will happen to her in the future.

- A man never questioned whether he actually wanted children or marriage; yet he is pursuing both blindly anyway.

- A proudful soldier feels the force of duty to his country and government; he can, therefore, justify his oppression of minority groups.

The subject in each example had a choice. But, instead of choosing freedom from their situations, they chose to renounce freedom itself.

According to Sartre, you always have a choice as long as you have conscious faculties; and an appeal to anything beyond yourself that stops you from making it is an attempt to deceive yourself. Freedom does not concern the success or the failure of the choice nor the consequences thereof: you can choose to look both ways before crossing the street and be just as likely to be hit by a car. Thus Sartre argues that, wishing for something to be so above the facticity of the world, is a form of bad faith: an attempt to transcend a situation subjectively without fidelity to the facts.

‘I can do anything by just wishing it’ is nuanced from the more-negative ‘I can’t do anything about it’; nonetheless, they are both born in bad faith. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre writes of the more-positive aspect of bad faith (which he actually saw as being constantly in concert with the other form of bad faith, and thus does little to separate the concepts), saying:

Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre at a fairground in Paris, June 1929.

To be your own ‘transcendence’, to feel beyond yourself in complete control, you must recognise that ‘you’ are a transcendence, but in bad faith you lie to yourself about it. Today this form of bad faith is often seen in full force, given our positivity-centred, postmodern, social-media-driven culture.

But I should be clear: Sartre opposes either form of bad faith in line with his opposition to our oppression. The way to combat it, he says, is to live authentically: not by embracing one’s own biology or historical context but by clarity of reflection, responsible action, and mutual recognition of each other’s freedoms.

Sartre exemplifies inauthenticity in Anti-Semite and Jew, albeit controversially, by arguing that inauthentic Jews ignored racism and internalised negative stereotypes so as not to see the truth in their horror:

But, as we consider whether we live authentically or inauthentically in response to accusations of bad faith, how can we distinguish one from the other? Maybe the astrologist’s assessment of their life was true and lucid; perhaps the husband and father felt clear in his motives to get married and have children; and it’s possible the Jew sincerely held unbecoming opinions of other Jews.

Again, Sartre’s arguments are powerful in getting us here, but they do not clear us of ambiguity between our socialisation and our freedom from it.

L'appel du vide

Jean-Paul Sartre lived and died in the city of Paris, dying on April 15, 1980 from an oedema of the lungs.

Sartre once said of consciousness that it was not something incomprehensible, but rather a ‘mystery in broad daylight’ (Existential Psychoanalysis). And I can think of no better phrase to describe his work.

Sartre thought psychologists had spent too much time concerning themselves with the unconscious-conscious divide, when the fascinating layers of consciousness had lain there before them. He switched his focus to the latter, explaining freedom and authenticity quite compellingly through the clarity of conscious reflection.

Sartre’s theories were caricatured. They were then integrated into our cinematic and commercial media: from Mad Men to House M.D. to The Good Place, the entertainment industry has sustained their life, especially his play No Exit, which has seen more adaptations than any of Sartre’s other works.

While Sartre’s fictional works have survived the ever-grinding consumerism of Western culture, his philosophy seems to have been, more or less, either dismissed or misunderstood, even by those who gave it a thorough study. His questions of freedom and bad faith chronically linger. But rarely is his philosophy examined for what it is, it’s there to be read.

Toward the end of Sartre’s career, though, when he published the first of his two volumes called The Critique of Dialectical Reason (the second volume was to be left unfinished), philosopher Michel Foucault said in an interview in 1966 that Sartre’s work was an ‘attempt by a man of the nineteenth century to think the twentieth century’; and, moreover, that his enterprise overestimated man in his ability to ‘adequate his own meaning’, when, actually, we all live on a vast web of political, theological, and moral structures.

Such criticisms were echoed by many philosophers who are well known today, such as Gilles Deleuze and Jacques Derrida, among others, several of whom had considered themselves, at one time or another, to be students of Sartre.

As Sartre found himself more and more sick, he spent less time defending himself as postmodern movements rejected and discarded the existentialism he spent his whole life developing.

In our culture today, imperfect as it is, this tendency to dismiss existentialism is now more of a matter of course than anything. Indeed, existential philosophy is often considered something of a joke to be caricatured on social media: a self-concerned journey of angst and despair, cast in black and white and veiled by coils of cigarette smoke, and born in the chasms of meaninglessness and death.

But we should resist throwing Sartrean philosophy to the void. Today we can see existentialism is slowly making its return as postmodern movements begin to fade and are usurped by reinvigorated desires for something more authentic. Perhaps, we can avoid the mistake of Foucault or Deleuze, and we can give Sartre a second chance. And perhaps we can do so by finally giving his work a serious read.