Whiplash: The Duality of Greatness

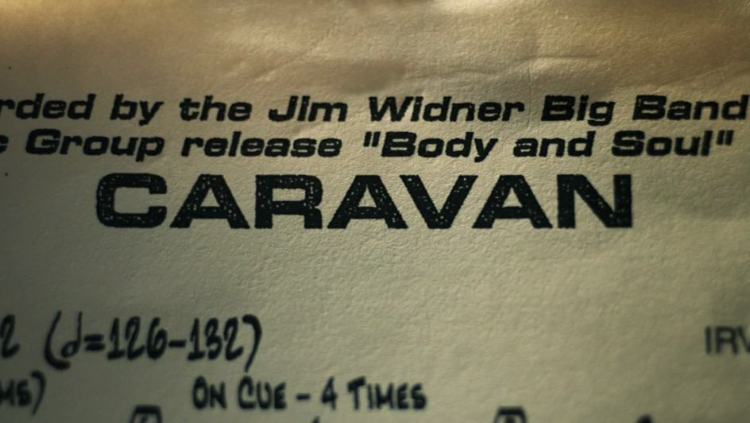

Featured image: 'Caravan', the musical piece that consummates Andrew's capabilities as a musician and concludes his pursuit to greatness. Was the journey worthwhile? (Sony Pictures Classics)

The path to greatness, as a narrative, has already reached the creative and entertainment industry at large ‘How far should we go to fulfil ambition?’ We are asked. Beneath this question is something human, something dark.

No investigation goes as far as Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash (2014), a film which follows the story of Andrew Neiman (Miles Teller), a music student at the highly esteemed ‘Shaffer Conservatory’.

A macro shot of a cymbal with Andrew's blood dripping on it. The picture symbolises the lengths Andrew is willing to go beyond comfort.

Whiplash portrays a strangely disturbing yet relatable narrative focused on the fine line between grit and obsession, between desire and purpose, and between mediocrity and greatness. As a film centred on these contradictions, it brings us closer towards humanity’s embodiment and the extents to which we are willing to break boundaries in pursuit of ambition, revealing an inner duality.

Greatness will come with sacrifice. Will Andrew let it break him?

Desire

The film begins with Andrew subconsciously diving deeper into his flow state as he practices in an empty room. He eventually finds himself being interrupted by Fletcher, who is looking for players for his band.

They say that the first scenes of a film define the essence of its narrative. In Whiplash, the desire for greatness is signalled early on as the major theme. Andrew practises alone with focus and determination in the opening scenes, seeking to push the boundaries of his own capabilities as a drummer.

From this, we learn that he yearns for an opportunity to be heard. With some fortune, he gets it. Andrew catches the attention of Terence Fletcher, the leader of the school’s concert band.

Remarkably, by around four minutes into the movie, to be exact, we are not even shown a glimpse of Andrew’s life outside of music.

Later, based on a handful of scenes, he is shown to live a simple and comfortable life with his father, Jim. However, as Andrew unravels, we learn that his family suffers from a lowly reputation among their middle-class community. Jim is divorced, a failed writer, a high school teacher—just your average guy. And, now, falling further from impressing his friends, his son is trying to be a musician.

It is evident that the intention of Chazelle, by introducing intense family moments after we know of Andrew’s passion for drumming, was to realign our focus: we learn of Andrew’s desire to obtain what lies beyond what is expected of him first; then, in reverse, we see what he’s leaving behind on the peripheries of that desire.

A closer look at Andrew

A hopeful Andrew smirks; he might finally get his break in music.

In the opening stages of Whiplash Andrew is portrayed as a vulnerable yet optimistic character. He seems capable of maintaining a balance between his passion for music and a life outside of it, visiting the cinema with his father and cultivating a possible relationship with a woman he admires.

Yet we learn that such comforts are momentary features of his life which orbit around an otherwise complex and divided individual. Andrew’s social encounters increasingly turn sour and are eventually replaced with more scenes of him existing merely as a musician.

On the flip side, these changes signify Andrew’s attempts to define his self-worth, a semblance of power. As an individual, he grows into the musical opportunities which are being presented to him. He takes actions which nurture a life worth living through music. And he flourishes a little.

Andrew’s newfound empowerment, however, causes fissures within himself. With his talents now being recognised, he must now decide between the familiar and a pursuit of greatness into the unknown if he is to finally make a name for himself.

Double it!

As we move deeper into Andrew's narrative, we begin to notice that his character is slowly taken off balance as his will is fuelled by Fletcher's approval. The challenge Andrew now embarks on necessarily requires him to meet the insanely high expectations of Fletcher.

For a moment, we feel relief for Andrew’s accomplishments: his hard work and effort are paying off. But, as we may suspect, it doesn’t last.

The sense of approval he feels from Fletcher is almost immediately replaced by doubt, whose standards always demand more. Andrew has to raise his game if he is to gain further approval.

It is at this stage of Andrew’s development that some serious questions about self-worth and recognition are raised, not least: is self-worth relative to what’s expected of us or is it born within?

In life, it is generally accepted that having passions is a good thing and that being ambitious is praiseworthy. What is not quite as clear, however, is how far we should take our ambitions to prove ourselves above adequacy: what is successful enough?

We work to the standards of the systems we enter, but these standards evolve with us. Albeit, we may hold an initial intention only to stand out a little as a 1 in a sea of 0s, but we tend to want to rise above the crowd again sending ourselves to predetermined dooms of greatness.

Abraham Maslow, a 20th-century psychologist known for creating the theory on the ‘hierarchy of needs’, was convinced that within each of us exists an impulse to achieve greatness in an urge to move toward what he called our ‘highest possibilities’. However, Maslow believed that we also fear our greatness more than we desire it and coined this phenomenon the ‘Jonah Complex’.

But this fear of self-actualisation does not apply to the case of Andrew Neiman, who is presented as a character who vigorously prioritises musical prowess over everything else. He is unbounded in his pursuits now; he has no fear of leaving anything behind.

Not quite my tempo

Fletcher obscenely asks Andrew a series of questions in what is amiably known as one of the most-defining moments in the film.

The standards Andrew must reach now are immense. Andrew has to want this. Does he?

‘Were you rushing or were you dragging?’ Fletcher asks Andrew as Andrew struggles to play the song ‘Whiplash’ at the correct tempo.

FLETCHER: 'Start counting!'

ANDREW: 'Five, six, seven—'

FLETCHER: 'In four, dammit! Look at me!'

ANDREW: 'One, two, three, four—'

[Fletcher slaps him the face]

ANDREW: 'One, two, three, four—'

[Fletcher slaps him again]

ANDREW: 'One, two, three—'

FLETCHER: 'Now, was I rushing or was I dragging?'

[with respect to Fletcher's slaps]

ANDREW: 'I don't know.'

FLETCHER: 'Count again.'

ANDREW: 'One, two, three, four—'

[slap in the face]

ANDREW: 'One, two, three, four—'

[another slap in the face]

ANDREW: 'One, two, three, four.'

FLETCHER: 'Rushing or dragging?'

ANDREW: 'Rushing.'

FLETCHER: [yelling] So, you do know the difference!

The differences in tempo between Andrew’s successive failed attempts and the correct tempo are non-existent to the untrained ear—such are the standards Andrew has to meet now. He finds that the arena of greatness is filled with tension and expectation and, understandably, he is struggling to find the prowess of music Fletcher requires in him immediately.

Fletcher, meanwhile, in his role as mentor, continually shows acts that are contradictory in nature to impose his will upon Andrew. In the ‘rushing-or-dragging’ scene (above), it becomes unmistakable that Fletcher uses his position of power to instil perfect conformity in Andrew’s playing. However, throughout the film, we are shown a student who seeks to be different and exude individuality from the rest of humanity (as mirrored by the music industry). And Fletcher seems to support this and even claims his harsh authority is necessary to create brilliant individuals. But the force provided in Fletcher’s arbitrary motivations support the idea that Andrew cannot win either way.

It seems that Fletcher was intentionally placed as an instructor and a conductor to symbolise the control that he obtains over his band. Andrew is positioned as only a follower of directions who is becoming lonelier and more isolated in his desperation to impress him.

But Fletcher’s ambiguity is exposing a greater division: that within each of us is an individual who yearns for both conformity within a system and individuality from it.

Blindfolded by technicality

Practising with him for the first time, Andrew discovers the unconventionally brutal teaching methods of Terrence Fletcher. Does he rest from the battle and accept defeat, or does he pursue the part of himself that wants to attain greatness?

Music is often seen as a sensual medium that either exudes, explores, or is created from the senses. But Whiplash provides the other side, dwelling on the importance of technicality more than its experiential impact.

Fletcher pushes Andrew to his technical edge without any interest in what Andrew wants to express in his drumming. A contradiction of some sort, between innate musicality and music theory, is therefore at play.

In Gordon Graham’s Philosophy of the Arts: An Introduction To Aesthetics, on music and emotion, Graham states the following:

Increasingly, we see in Andrew someone who is blinded by technicality, suggesting he is striving to attain greatness for its own sake. This begs the question: in losing himself, is he becoming anyone with emotions worth having?

A descent into madness

As the narrative draws us nearer to its end, we are shown a version of Andrew walking at the edge of sanity as he slowly lets his desire to be recognised devour the entirety of his being.

With his heavy breathing intensified to signal a violation of his old self, we are raised with a question that haunts the waking minds of those who resonate with the turn of events: if the path to greatness necessarily leads to a descent into madness, should we be pursuing it at all?

There is always more to achieve and infinite more ways to be better. It’s also true that complacency shallows our vision; but, conversely, a desire to succeed can be unhealthy to the point of self-destruction.

The most-telling part of Andrew’s descent starts when he is placed in one particular unfortunate situation. Unhinged and on the brink of his own consumption, he is only able to gain this clarity at the point of extremes.

Rushing back to a competition after forgetting his sticks, he is involved in a road traffic accident. Yet, exhausted and injured, he insists on playing in the concert. Andrew’s desire to be recognised is so great, at this stage, it has been fully unleashed by Andrew.

Fletcher is persuasive and compelling, but Andrew seems to choose all of this: he chooses to return to the pressure and uncertainty of ambition every time. What does this say about him (and us)? Is Andrew a victim of manipulation and abuse? Well, yes. But, in some sense, Andrew is also a victim of his own torture. And what will become of him when he finally consumes himself?

As Andrew drifts closer towards the abyss of his desires, we begin to contemplate the beginning of his journey. Presently, we are shown a version of him on the crossroads between (a) pursuing passion, within some notion of reason, and (b) chasing down an idea of success, with a disturbing disregard of what is safe.

Through these circumstances, does he truthfully find a way or does he lose himself even further?

It can be said, however, that destruction is necessary to make way for the new; that there is a need for chaos, especially for those who have lived in conjunction too long with comfort and safety. In it necessary insofar as they can break free from pre-established notions of their identity on their terms.

So, perhaps, from one polar end of his existence to the next, Andrew leaves a listless, drab, and disappointing existence behind to birth himself anew, arguably with too much of this negative, egocentric, and passion-hungry desire.

With greater instinct, Andrew’s desires are now shaped by the untamed. Whether he should allow this or not, he doesn’t ask. He permits himself to be lost in another extreme.

Who is the enemy: Fletcher or mediocrity?

Andrew is kicked out of the band. Fletcher is removed from Shaffer. A confounding act of vulnerability becomes of Fletcher, who reveals his methods at Shaffer to Andrew. Can an expression of truth equate to a universally justified means to an end? Not by itself.

In the middle of what was going on with Andrew, in the development of Fletcher’s character, a thin line is being drawn between constructive criticism and abuse of authority. Fletcher claims he wanted Andrew to be brilliant, which required the strongest of mental challenges.

But, arguably, Fletcher was of the same power-hungry, influence-wielding dynamic as Andrew, projecting his will onto Andrew. Fletcher’s life would have continued in this vein had Andrew not joined the band to expose him. In nature, they were as bad as each other.

Although Fletcher’s intentions may have been good enough to encourage possibility for his students, this did not pan out well in terms of the consequences: Andrew was forced to leave the band and Fletcher was fired. There is also mental disruption to consider, especially to the minds of those who are not as tolerant as Andrew or those who do not have the hardiness to power through such traumatic experiences.

How do we classify the difference between an act of harshness that motivates to that which degrades self-esteem? I, for one, have experienced a Fletcher or two during my undergraduate studies and have considered them relevant to my progression as a human being, yet I continually question the extents of which I am capable of withstanding such circumstances.

Tragedy veiled as triumph

A dynamic interplay between losing and gaining control arises in the final scene as Andrew performs and Fletcher conducts. Each character is trying to overbear the other with their power.

In the end, we are shown a sequence of Andrew finally being able to break free from humility and pursue an image that he thought he built not for Fletcher but for himself.

Yet this was the image that Fletcher wanted to see in Andrew, too! Fletcher deployed his divisive methods on Andrew and others to achieve exactly this kind of reaction.

Andrew and Fletcher live existences wherein they suffer conformity but still individually want to rise above it: one as a controversial teacher under the influence of gaining approval from audiences; the other as a talented student vying for fame and recognition above the rest. But they now do this together: by trying to overpower one another, they each validate the other’s individualistic existence.

As he performs with Fletcher’s band again, Andrew is finally able to gain a consciousness towards having control. But the events only divert our attention away from the possibility that he is operating under an illusion of freedom. Was Andrew able to actually liberate himself from Fletcher’s expectations and succeed in becoming one of the greats? Or is he yet another one of Fletcher’s subjects?

On one hand, it may seem that Andrew is now free and now great, but as Andrew continues with his drum solo, we cannot ignore the look on his face that exposes his subtle desire for wanting a hint of approval from Fletcher. Granted, Andrew took the opportunity to momentarily gain control, but his strength was never in a position of independence from his idea of needing to mean something to his mentor.

Was Andrew, then, able to attain freedom from mediocrity since he himself, like many others, became a slave to greatness? Perhaps the idea of mediocrity only becomes frowned upon when it is imbued with a set of expectations which we are familiar with.

Success, in many ways, is better understood as to not end with a narrow path towards a single goal, rather an accumulation of all that embodies human existence: we define our vision and grow into it, but this rarely or never separates from the approval of others. ‘Hell is other people,’ as Sartre wrote.

The cost of greatness

On the detached human condition: 'I want to be one of the greats. And because I'm doing that, it's going to take more of my time. And this is why I don't think we should be together.' — Andrew Neiman

Before I finalise my thoughts, I want to take a step back to reflect on Andrew’s story, with particular regard for one scene.

Pursuits of greatness have a tendency to cultivate a feeling of loneliness and isolation. The more we establish a difference and individuate ourselves from the majority, the more we lose our connection to the crowd, therefore stimulating fear and anxiety through ambiguity.

In this particular scene (depicted above), Andrew starts a conversation explaining his reasons for breaking up with Nicole, the woman he met at the cinema (towards the start of his journey). This conversation is seen to provide a straightforward perspective on success: being with Nicole would have deprived Andrew of fully realising his potential.

I originally intended to include this scene inside its chronological appearance in the film, but it provides a relevant insight into realisation of success after understanding Andrew’s spiral into madness. He is losing everything for greatness; yet our ideas of it are so compelling on an individual level.

With that said, do we choose the path to greatness or exist with the meaning of comfort? Or is there a possibility of finding purpose by acquiring both simultaneously?

An inversion of morals

At this point, we learn to appreciate subtle glimpses of the mundane in a sea of overwhelming rudiments of desire.

To conclude my sentiments, it could be argued that greatness is but an illusion created by our instincts to succeed and overbear. But in the direction of the late 20th century, up until the present, we have seen and experienced a shift in mindset with regard to what the author Colin Wilson calls as the ‘unheroic hypothesis’ of ‘The Age of Defeat’.

Most of us, if not all, have been accustomed to vulnerability or futility and have embraced the existence of such qualities as being a part of an embodied experience. At the same time, we coexist with relics of heroism, living during an era where courage is characterised as an acknowledgement of weaknesses. In a Nietzschean inversion of morals, such boldness is no longer a virtue but an act of self-preservation we no longer require—or so we thought.

Despite the emergence of this new mindset, the desire for greatness has not faded in our minds. There could be a shift in our perspectives, different from those of Andrew and Fletcher’s notions, where we examine ‘greatness’ in terms of purpose more than impact. But, still, the essence of wanting to be great would remain engraved on our subconscious.

Thus, as Whiplash transitions into momentary darkness in its last few minutes, we’re left to make sense of its narratives. To what degree is a pursuit of greatness, however we define it, still considered to lie within the spectrum of sanity and preserved self-identity?

I wonder, if given the chance to live a reality similar to that of Andrew’s, would I have taken the bus to the band competition or scheduled a date at the movies instead? The answer is not clear.